SCOTT Pruitt heads the US Environmental Protection Agency. Last year he was planning to visit Australia, and the proposed agenda did include a two-hour roundtable with me and colleagues from three Australian universities.

Some of this is reported today in The Guardian.

Along with the inference I’m a nutter – because I have accused the Bureau of Meteorology of corrupting the temperature record.

The Australian public do have much confidence in the Bureau, as they have in the past had confidence in the Commonwealth Bank, Catholic Church – even the Australian cricket captain.

In the case of the banks and the churches, ordinary Australians were complaining for years before any action was taken. Now, the authorities are asking how could we have been so-misled for so long? Why was nothing done sooner – and why was the mounting evidence of wrong-doing ignored.

For some years I have been asking for an open, honest and independent inquiry into the operations of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology. In 2015, I wrote to the Auditor-General of Australia suggesting a performance audit with terms of reference to include: consistency with its own policies, and reliability of methodology. At the time my primary concern was the remodelling of temperature data through a process known as homogenisation.

In response, it was suggested I direct my concerns to Dr Ron Sandland AM, who at that time was chairing a Technical Advisory Forum to review these same issues, that I had previously raised with then Minister for the Environment, Hon. Greg Hunt MP. It was already clear to me that Dr Sandland and his team were undertaking a most cursory review and not working through a single example of homogenisation. I nevertheless made a submission to Dr Sandland’s Forum that has never been acknowledged.

As I detailed in a letter sent just this morning to Australia’s Chief Scientist, Alan Finkel, my issues continue to be less with the actual policies, protocols and best practice manuals already in place, but with increasing evidence these are being systematically ignored. This is exactly the issue that the current Royal Commission is finding with the banks – because it is not believing the documentation, but actually working through examples and establishing what happens in practice.

The Guardian would do well to consider my evidence closely – to stop parroting assurances from Bureau chief, Andrew Johnson, and work through an example of how data is remodelled.

I could detail many other areas of operation in which the Bureau blatantly and systematically disregards its own specific and correct policies.

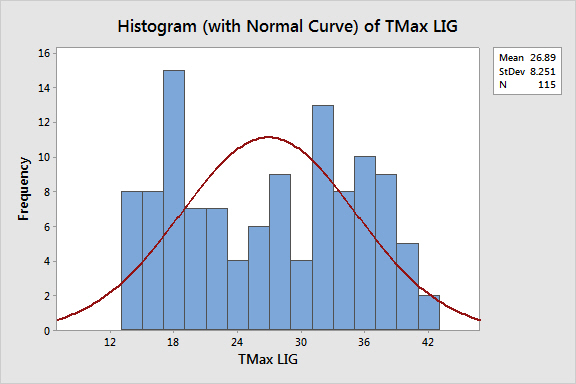

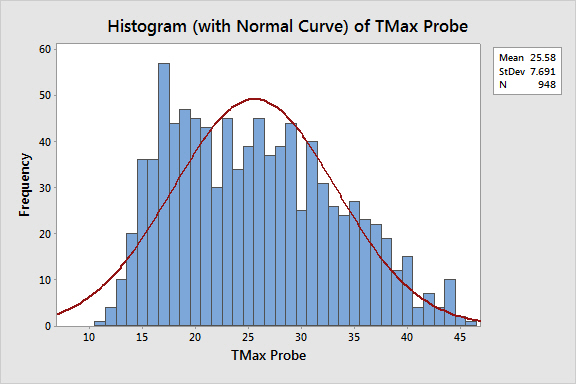

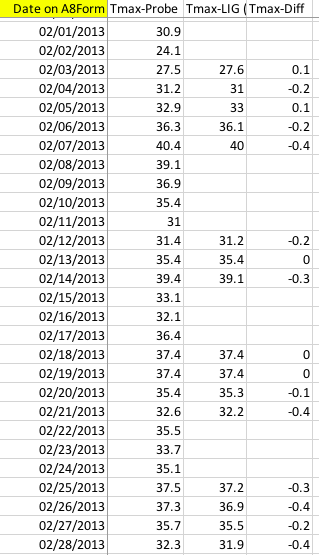

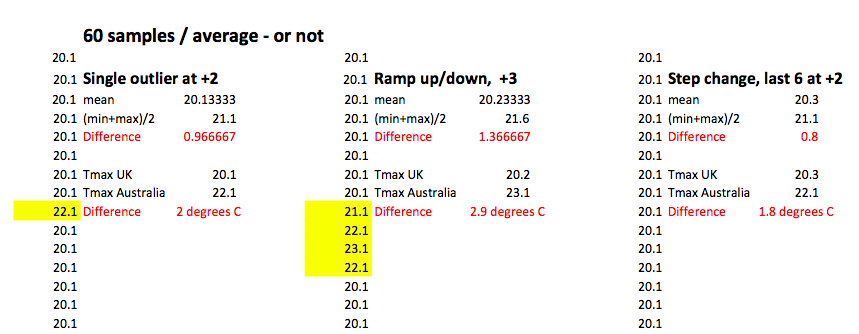

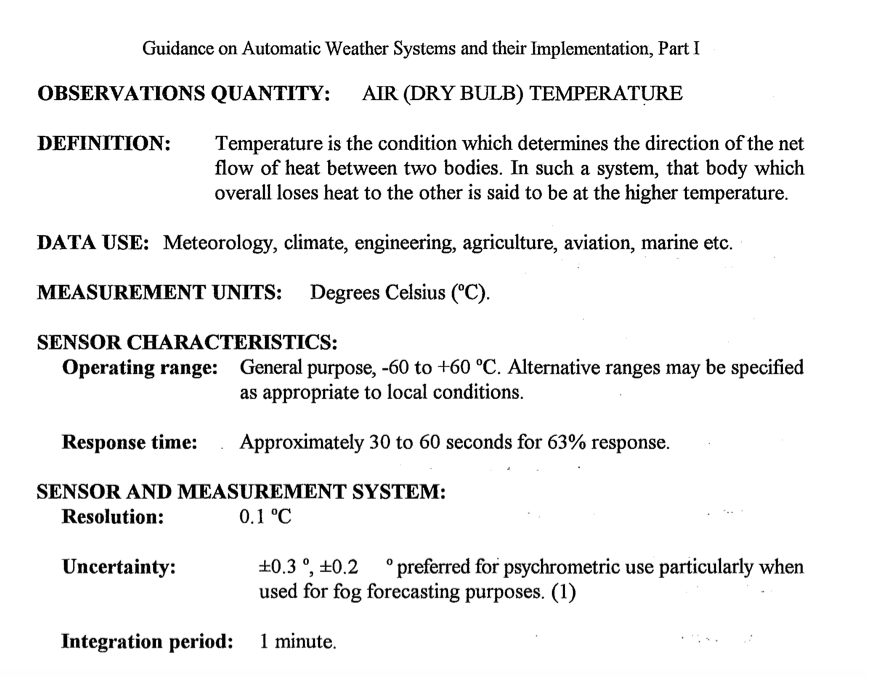

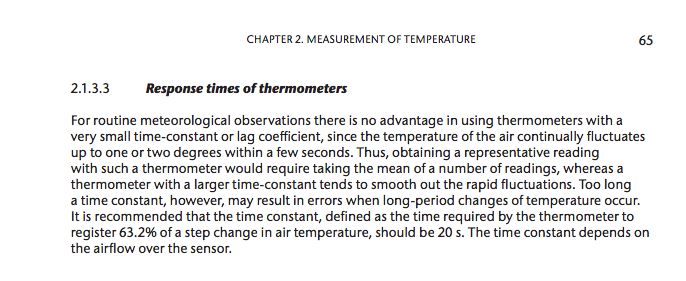

The one issue that I detailed for Alan Finkel is the way temperatures are currently measured in automatic weather stations by electronic probes. This goes to the heart of the integrity and reliability of temperature measurements recorded by the Bureau, subsequently homogenised, and incorporated into international databases – including those relied upon by the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

I may have raised exactly this issue with Scott Pruitt. He would have been arriving in Australia in September, at about the same time that the Bureau handed down an internal review in which it admitted to having set limits on how cold temperatures could be recorded at both Goulburn and Thredbo in south eastern Australia.

When I first detailed the evidence for this at my blog in early July – I was considered a nutter by many. But after Alan Jones interviewed me on radio 2GB, and despite the Bureau strenuously denying it was setting limits, Environment Minister The Hon. Josh Freydenberg MP did asked for a review of the operations of the Bureau’s automatic weather stations.

On 7th September, just as the report was published, the Minister phoned me to let me know that the Bureau’s internal investigations confirmed that Goulburn and Thredbo were the only sites where temperature records had been affected by the inability of some Bureau automatic weather stations to read low temperatures… limits had indeed been set.

What are the chances? Of the Bureau’s 563 weather stations, I had stumbled across the only two with problems.

Guardian reporters like Adam Morton may continue to be dismissive and suggest those who doubt, including Scott Pruitt and me, are fools. But the real fools are those who fail to see that climate science falls well short of Popperian standards, rather engaging in all manner of tactics to defend absurd practices as detailed in my letter this morning to Alan Finkel. Indeed, it very much resembles the model of scientists behaving badly as described by Paul Feyerabend.

It is unfortunate that Scott Pruitt had to cancel his visit to Australia when Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas gulf coast – but the evidence against the Bureau for corrupting the temperature record remains.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.