Knowing the truth has always been a challenge requiring an amount of discipline. And it is getting that much harder in this age of disinformation. How can we distinguish reality from fantasy, truth from propaganda?

Science used to be so useful for this. But many government-funded reef research programs now amass data to prove a bad impact from global warming, and other things. There is not much hypothesis testing as such – not even about how coral growth rates are affected by increasing sea temperatures.

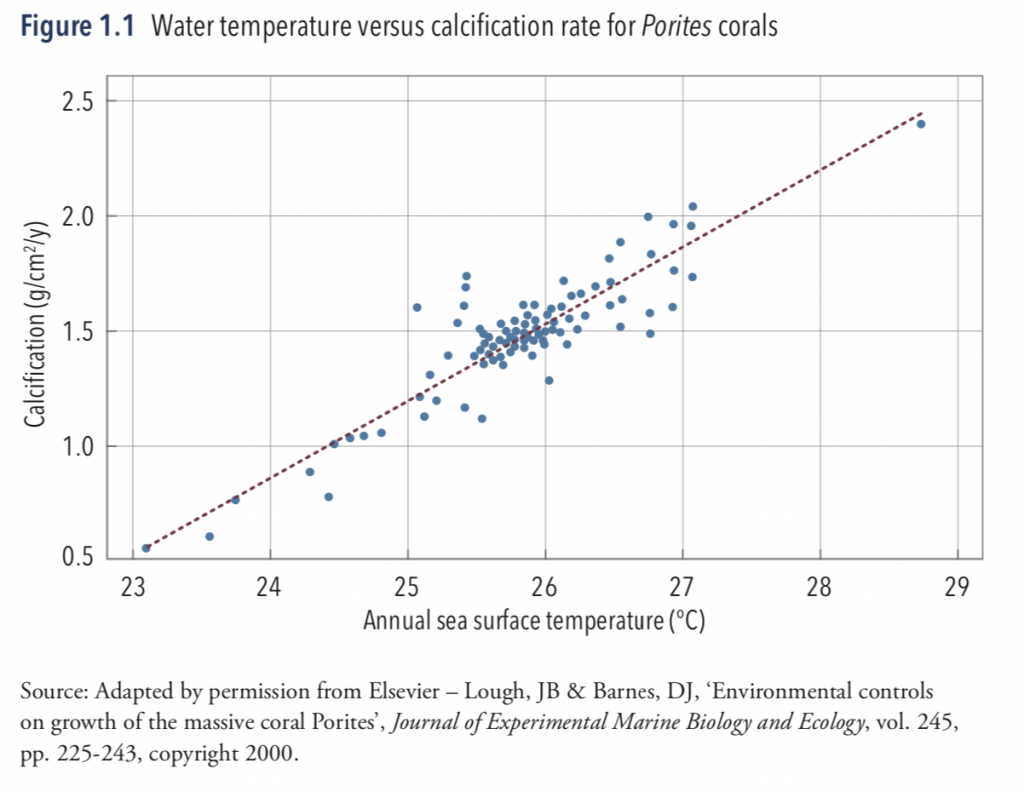

Coral reefs are amongst the most diverse, species-rich and spectacularly beautiful ecosystems on Earth. The largest and best known of these is the Great Barrier Reef and there was once a program of coring, with an annual average growth rate reported for the entire Great Barrier Reef. In the beginning it was hypothesized that as temperatures increased coral growth rates would increase too, which is a good thing – right?

In the beginning the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences (AIMS) sampled the really old large Porites. These are the bolder corals with distinct annual bands – variations in the density and length of these annual bands are an indication of changing growth rates.

Then, after 1990, they started mixing up the young (less than 15 years old) with the old (more than 100 years old) samples, which generated some confusing results. A study published in Marine Geology (volume 346) that used only data from the large old corals showed an increase in calcification rates (coral growth rates) over the last 100 years, rather than a sudden drop off after 1990.

Then AIMS just stopped coring the really old Porites and stopped calculating an annual average growth rate. It is now 16 years since AIMS published an average coral growth rate for the Great Barrier Reef. This makes it that much harder to know if the Great Barrier Reef really is dying – or if this is just scare mongering to generate research funding.

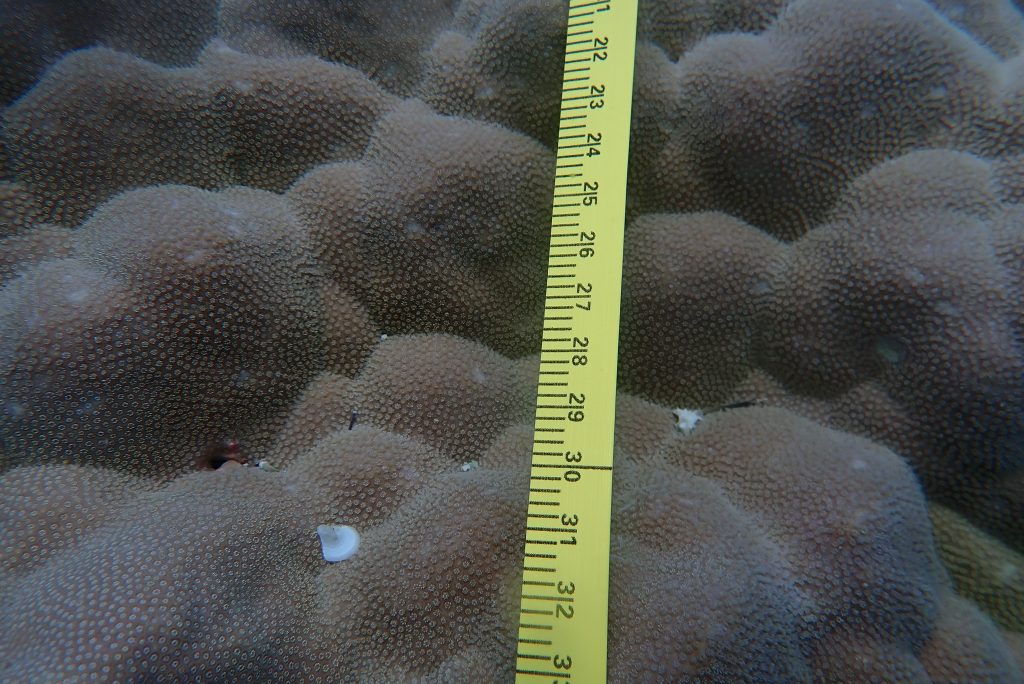

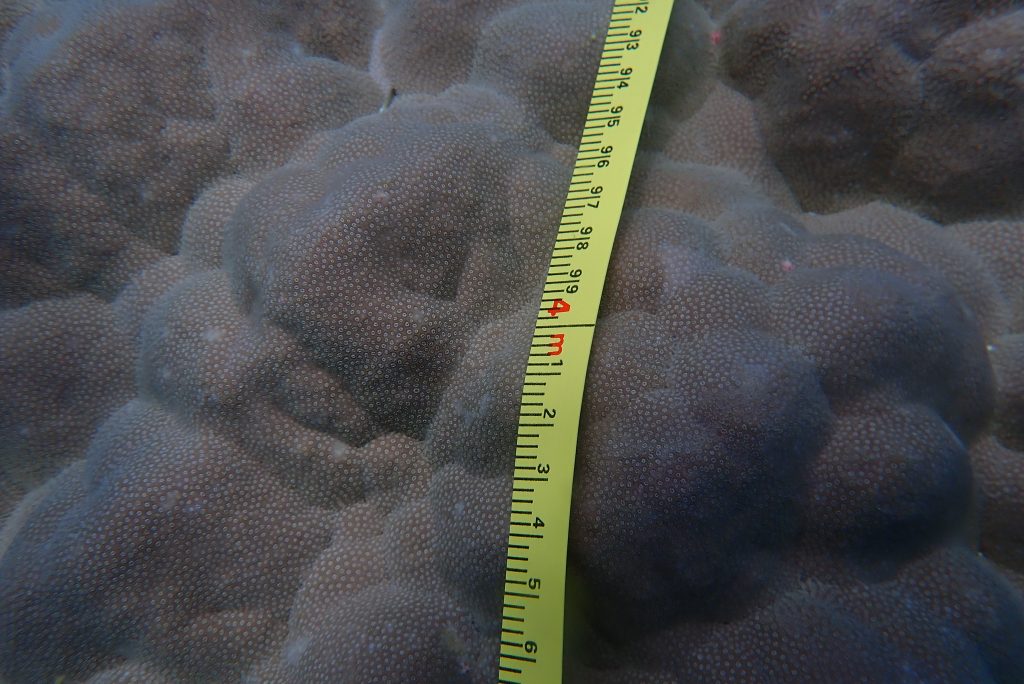

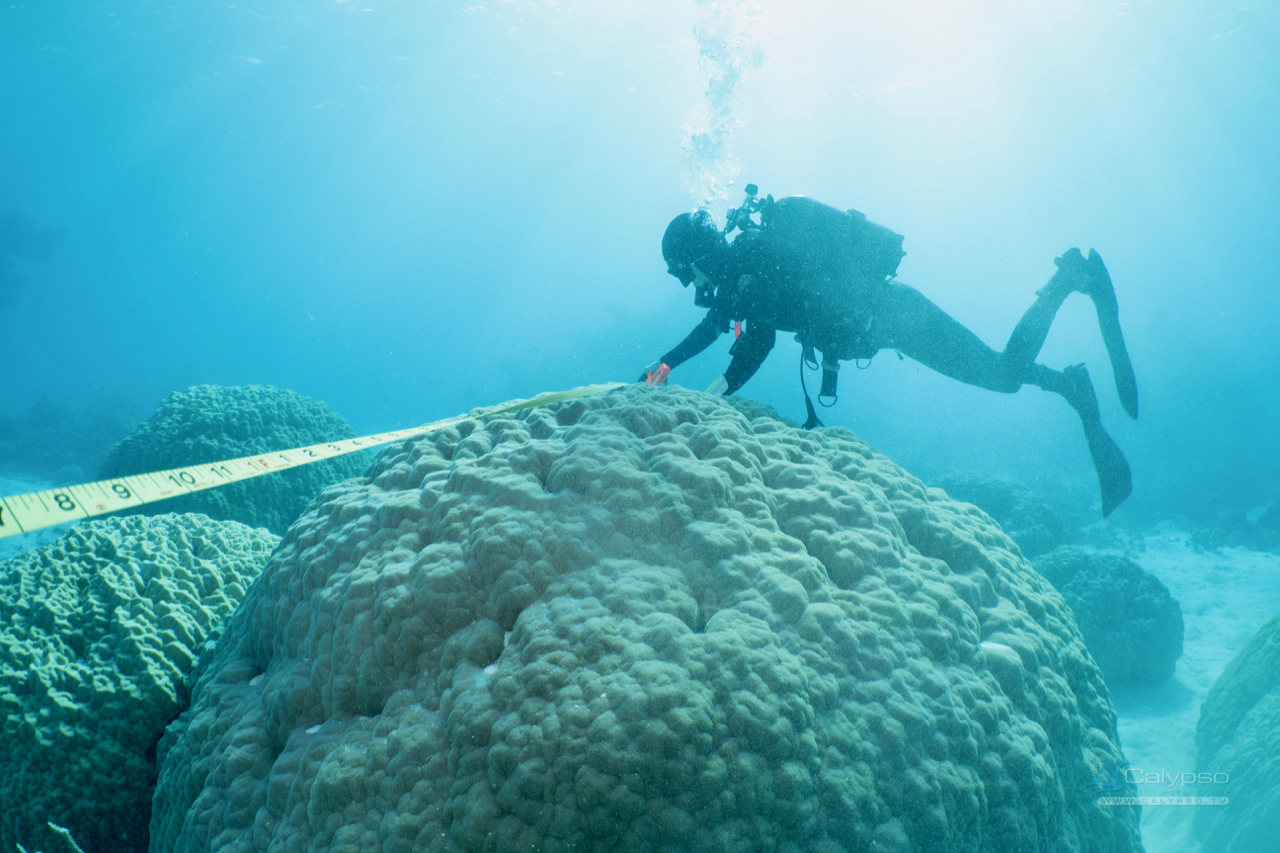

I think we should start an inventory of the oldest and largest Porites, to acknowledge and celebrate them. The largest massive bolder coral that I have measured so far is from Pixie Reef, just to the north east of Cairns.

Does anyone want to guess how high and wide this very large old Porites coral colony is? These photographs were taken on 25th November 2020.

I was wondering how we might distinguish the individual coral colonies: what we might call it? Then I remembered how it all began with naming cyclones:

It started in 1887 when Queensland’s chief weather man Clement Wragge began naming tropical cyclones after the Greek alphabet, fabulous beasts, and politicians who annoyed him.

After Wragge retired in 1908, the naming of cyclones and storms occurred much less frequently, with only a handful of countries informally naming cyclones. It was almost 60 years later that the Bureau formalised the practice, with Western Australia’s Tropical Cyclone Bessie being the first Australian cyclone to be officially named on January 6, 1964.

Other countries quickly began using female names to identify the storms and cyclones that affected them.”

I was wondering what we might call this massive Porites amongst the Pixies, and then I received a phone call from my dear friend Craig Kelly MP.

Following in the early tradition of Clement Wragge for cyclones, I though we might name this Porites after Craig – a truth seeker and for many an annoying politician.

These close-up photographs of Porites Craig taken at the same time as the wide-angle images, show that the corallite wall is still intact and some have their tentacles extended. So, we can conclude Porites Craig was quite healthy on 25th November 2020. If AIMS cored this coral we could know the true climate history of this place back perhaps 500 years.

Ends.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.