I am seeking feedback, including comment and corrections, on this draft blog post. I have previously sent an email to Richard Vevers (1 October 2021) and placed a request for more information at the Catlin Survey website (20 April 2021), without receiving any response from either. Irus Braverman was kind enough to reply to my email (30 September 2021) indicating that the photograph used in her book Coral Whisperers was provided to her by Richard Vevers.

If all science is either ‘physics’ or ‘stamp collecting’ as once suggested by Ernest Rutherford, I would argue that it is important that we not knowingly distribute fakes.

Corals Healthy, Photograph Bleached – Draft

Does it matter if the Internet is replete with fake photographs accompanying fake stories? Does it matter that these photographs keep children awake at night – worrying about climate change and the impending doom of our Great Barrier Reef?

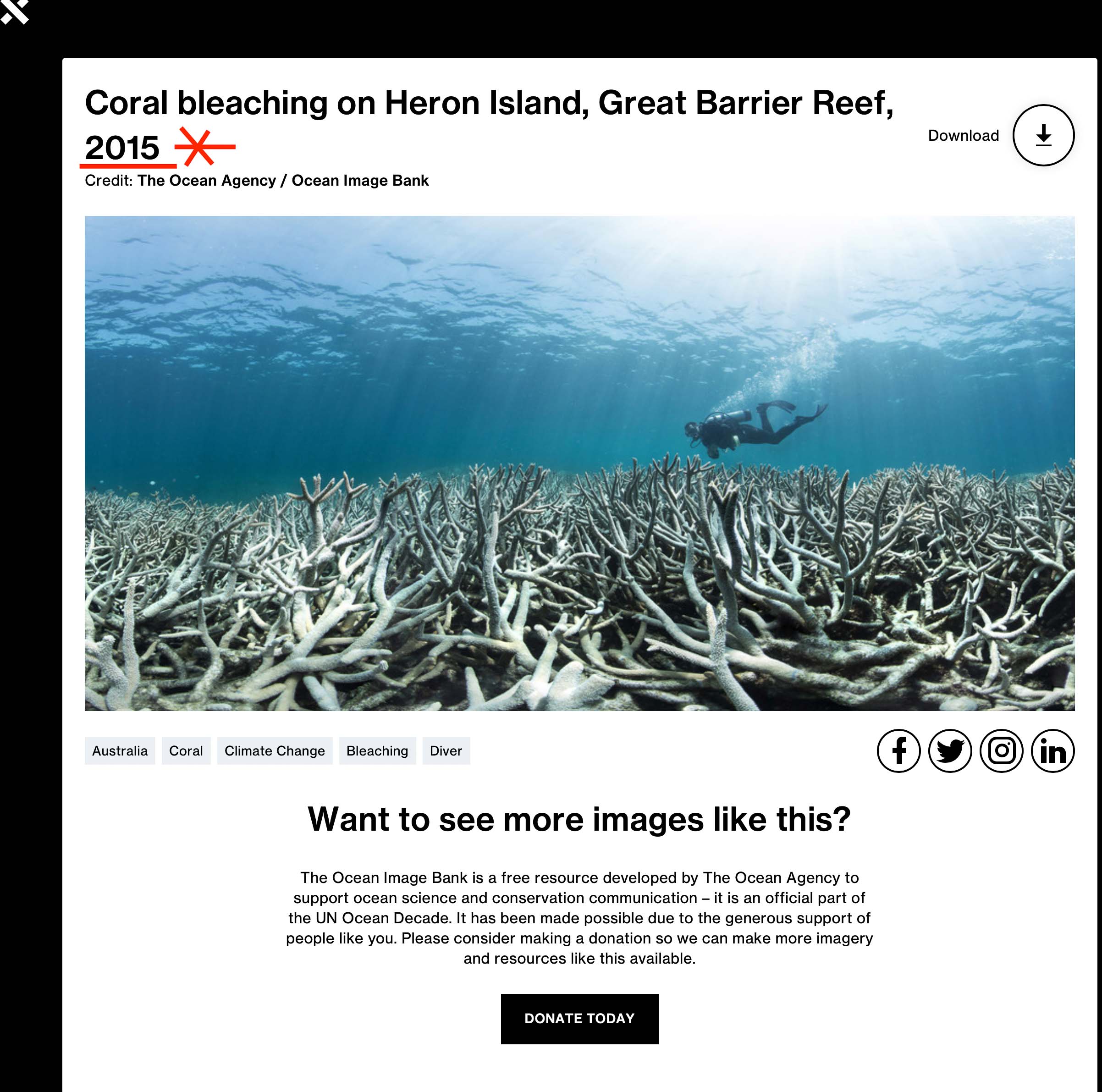

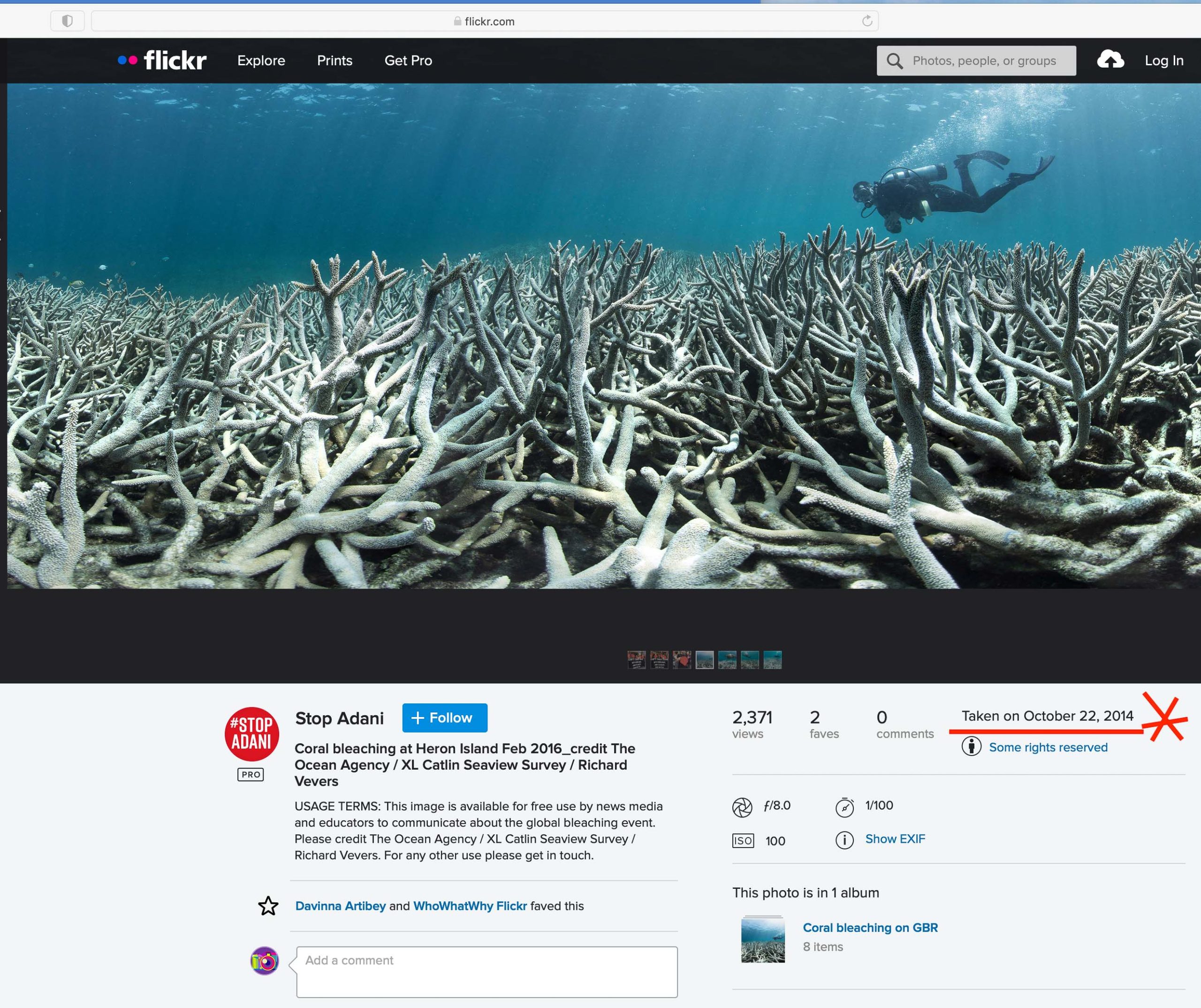

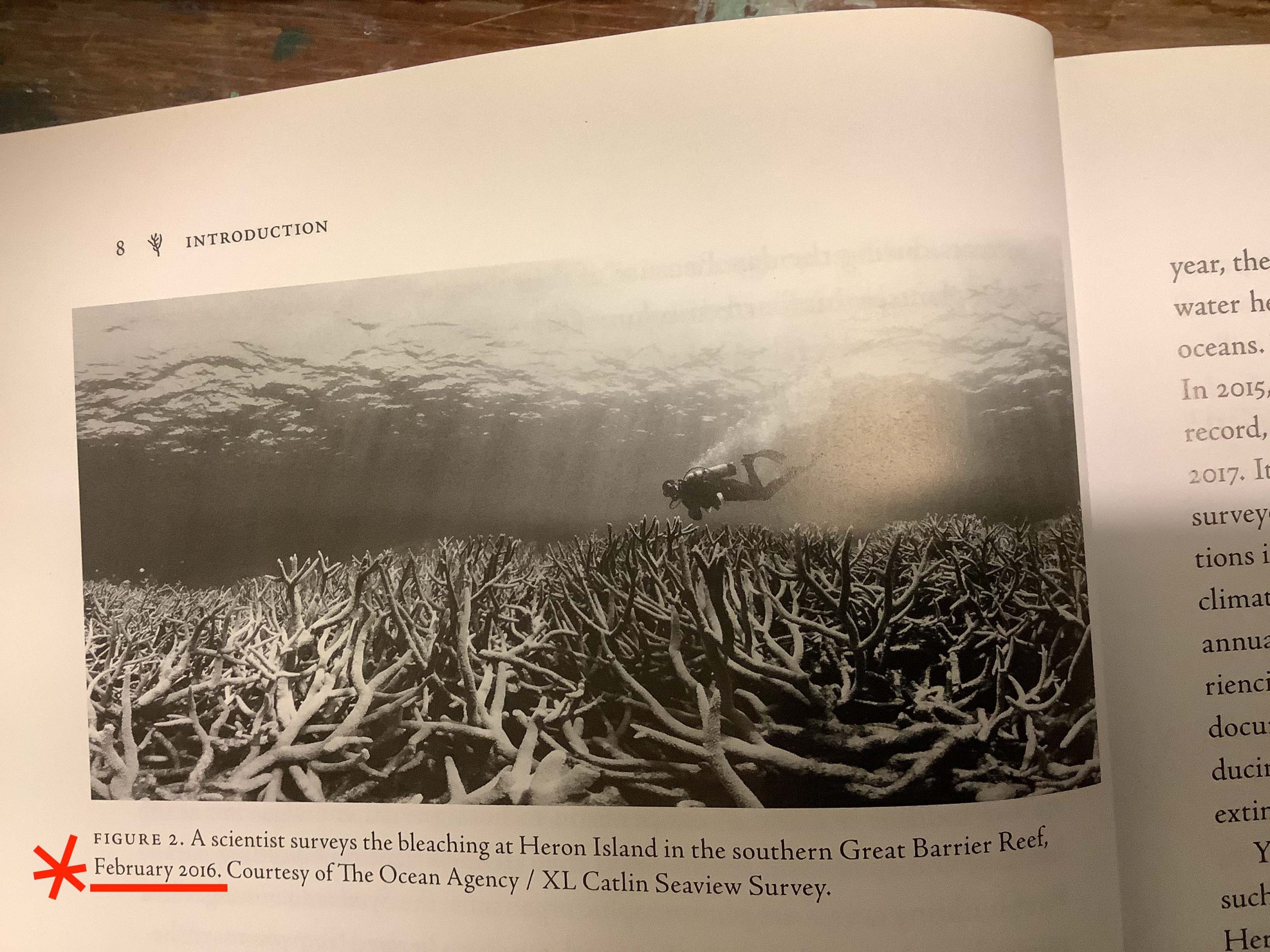

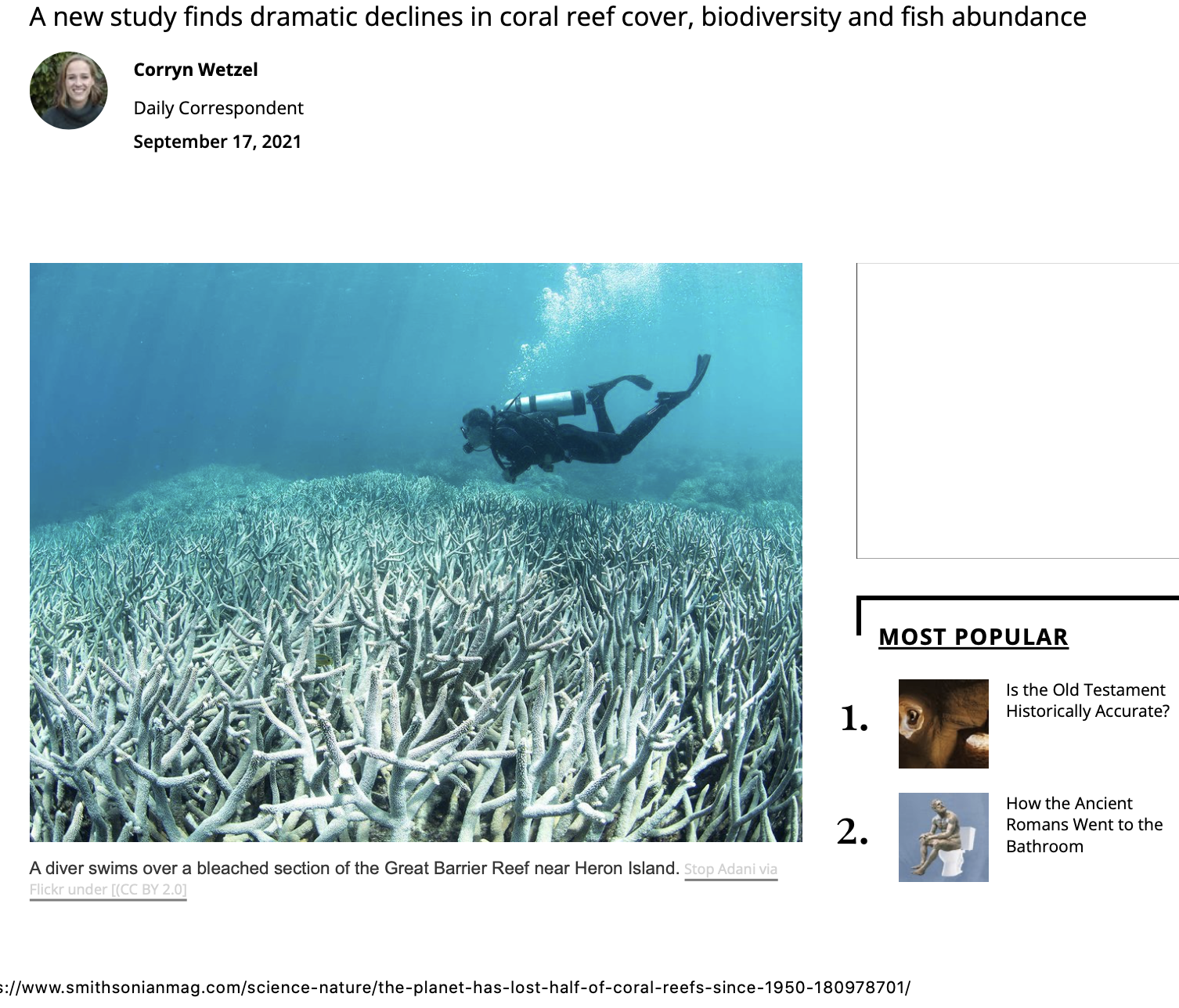

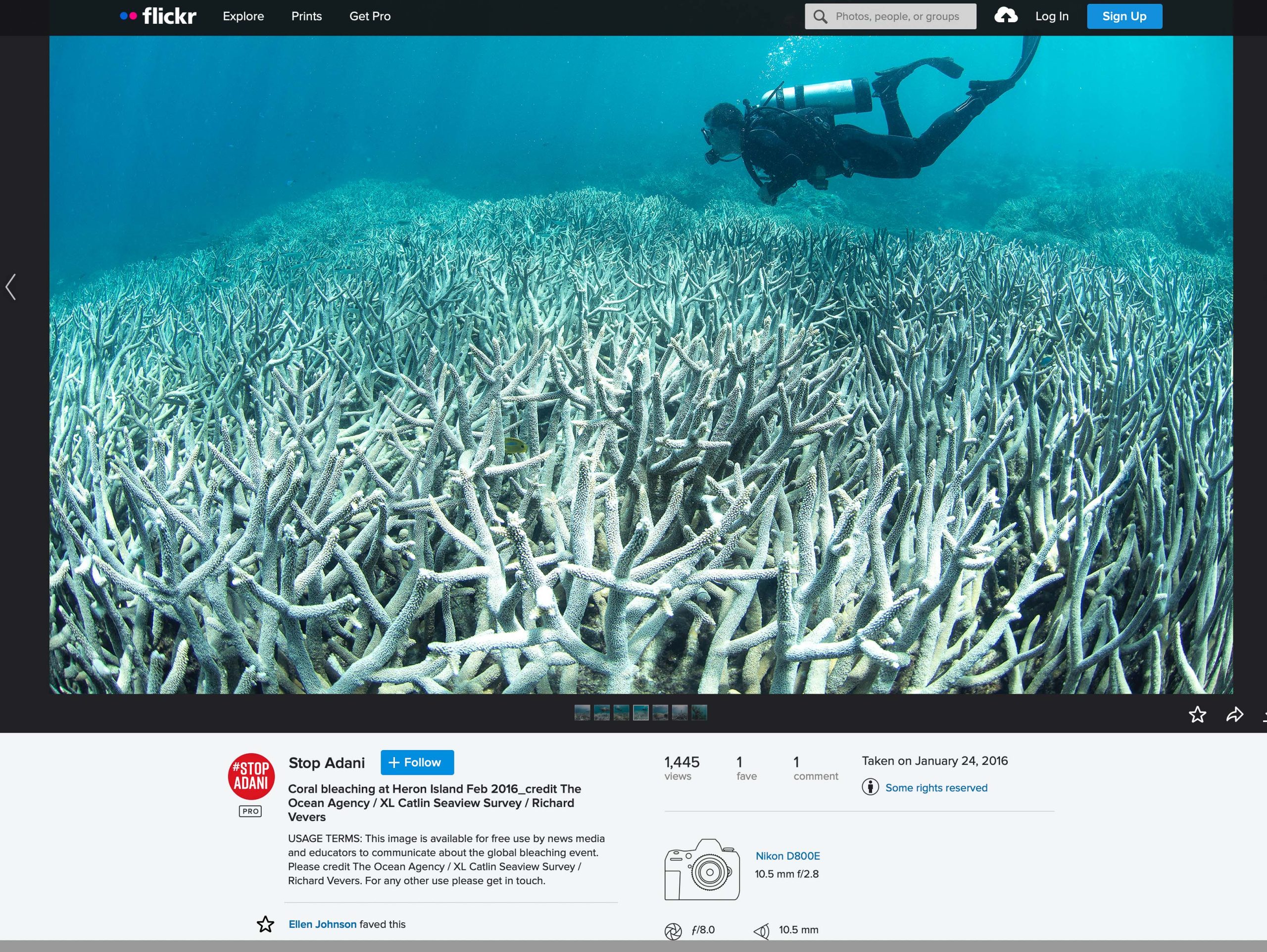

There is a photograph that has been promoted by Richard Vevers, the founder, and CEO of The Ocean Agency, a Washington-based international not-for-profit that is purportedly dedicated to marine conservation. It is described on his The Ocean Agency website as having been taken at Heron Island in 2015. On Flickr, the same photograph is described as having been taken in 2014, and in Irus Braverman’s book Coral Whisperers as having been taken in 2016.

At least two of these photographs must be incorrectly labelled.

It is the prestige associated with the XL Catlin Seaview Survey – touted as ‘the largest survey of the Great Barrier Reef ever undertaken’, ‘using unique SVII underwater camera systems’ and which commenced back in 2012 – that has given the photograph credibility.

The XL Catlin Seaview Survey was undertaken by The University of Queensland in partnership with Google, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the United Nation’s Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO), the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and others. The expedition visited Heron Island on 4 November 2012. The photographs from this survey can be viewed online, but this photograph is not among them.

According to the survey’s website, the XL Catlin returned to the Great Barrier Reef in 2014 following cyclone Ita, and again in 2016 following a mass coral bleaching. However, none of the 226,000 georeferenced coral reef survey images are publicly available from these expeditions.

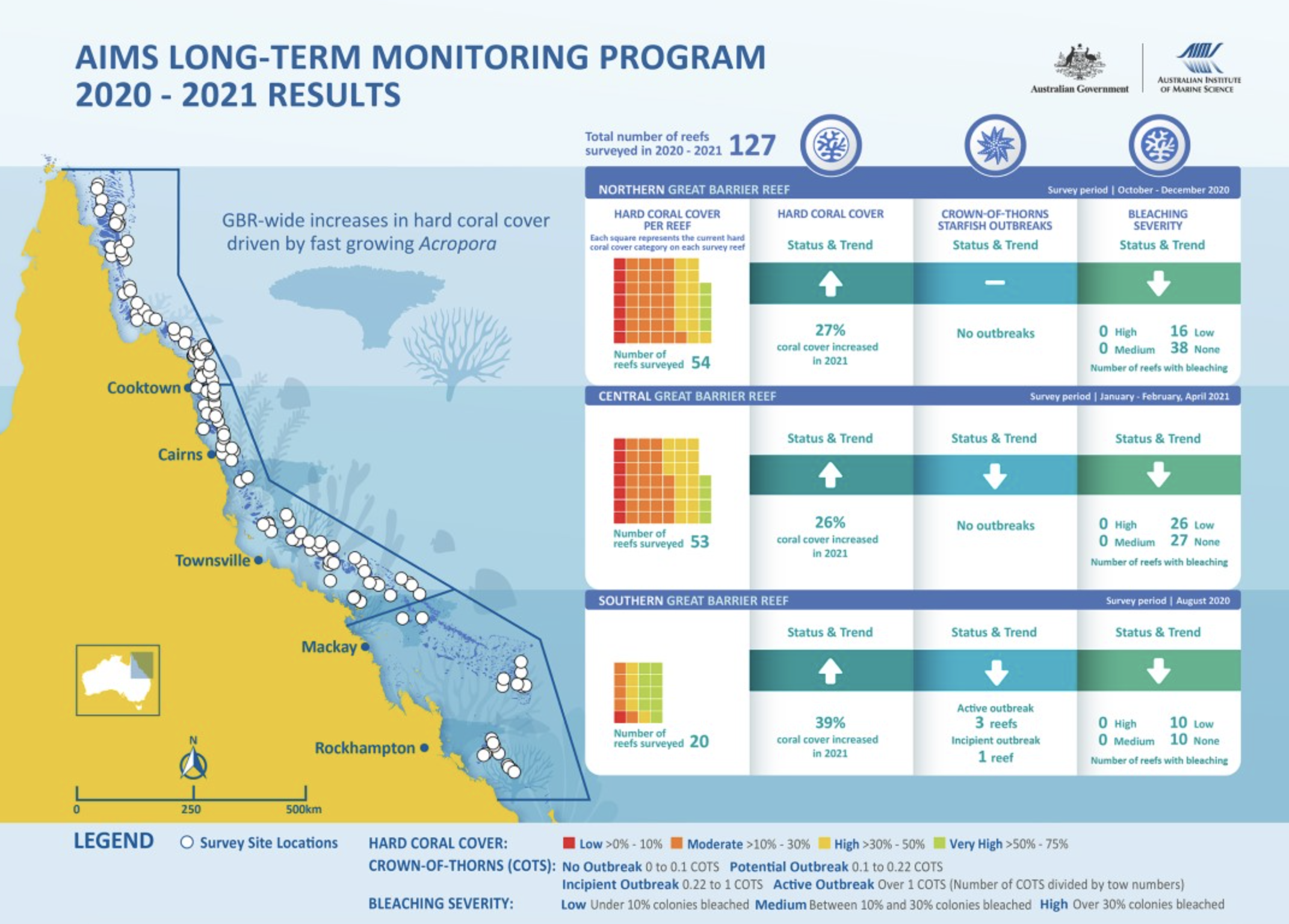

According to a different survey, which was an aerial survey undertaken in 2016 by Terry Hughes from James Cook University, it was mostly the northern section of the Great Barrier Reef that bleached in that year; however, Heron Reef, which is part of the southern Great Barrier Reef, did not bleach at all at that time.

In fact, the photograph was almost certainly taken on 22 October 2014, and it is not coral bleaching that is being seen. I hypothesise that the corals appear bleached because the photograph has been taken through layers of water that absorb light in the red spectrum and/or because some of the colour has been stripped from the photograph in post-production. Either way, it is not fit for purpose; it cannot credibly be presented as evidence of coral bleaching at the Great Barrier Reef in 2016.

Vever’s organisation has the official endorsement of the United Nation’s Ocean Decade, and the photograph may have been promoted by him ostensibly to support ocean science and conservation, and as evidence of bleaching at Heron Island in 2016. But this doesn’t make the image a true likeness. In fact, the photograph fits all the criteria of being a fake. I believe it does not show coral bleaching and there was no mass coral bleaching at Heron Island in 2016, or in 2015 or 2014.

I visited Heron Island earlier this month (November 2021) with underwater photographers Stuart Ireland and Leonard Lim. There we found the fringing reef to be healthy, including the fields of staghorn coral. We didn’t have the ‘unique SVII underwater camera systems’, nor the endorsement and sponsorship of a university, or Google, or the United Nations, but I did have the sense to place a colour chart among the corals to facilitate correct white colour balance in post-production.

It is evident from our photographs, with the colour chart providing some quality assurance, that the fields of staghorn corals at Heron Island are not bleached – not this year anyway. Maybe next?

Yet the XL Catlin Survey and Richard Vevers, via the Flickr website, continue to perpetuate the myth that they are bleached – most recently in the pages of the prestigious Smithsonian magazine.

Surely the children of the world deserve to know the truth about Heron Reef’s corals.

*****

Tues. 30th November 2021

– A Note from Arthur Day

Dear Jen,

Inspired by your request for help I offer the following:

Firstly, I used the uncorrected (white balance not corrected) native image you sent me the other day as one reference and adjusted the ‘fake image’ to match it.

That was EASY and did not require anything more of an adjustment than a global whole-of-image change, much the same as doing a simple white balance adjustment but this time mainly increasing the saturation and warming the colour temperature.

Secondly, I then selected two corresponding sets of detailed images from the before (fake) and after (adjusted) images to compare the corals with your unadjusted image (emailed to me).

The corals are definitely not dead. And, furthermore, allowing the possibility it was more sunny or shallower water when they took their shot, I think those details demonstrate a pretty-close match to your uncorrected ‘beige shot’ if also viewed in equivalent detail. Now, for additional confirmation they have faked the bleaching, contrast the diver’s yellow belt in my corrected images with the image as published by Ocean Agency and Flickr.

In summary:

1. The coral in that fiddled/fake image is definitely still alive.

2. It is important to observe that all (or much) of the original colour information remains in that altered image. It has just been greatly suppressed (‘washed out’) when the image was manipulated.

3. It should therefore be possible to restore the original colours by reversing the adjustment that washed them out. That is, at least to a large degree, it should be possible to restore the original colours. As I have done.

4. When we do that, it becomes apparent that this coral was alive and unbleached when the photograph was taken.

Regards Arthur

****

And so ‘Arthur’s image’ has become the feature image at the very top of this blog post.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.