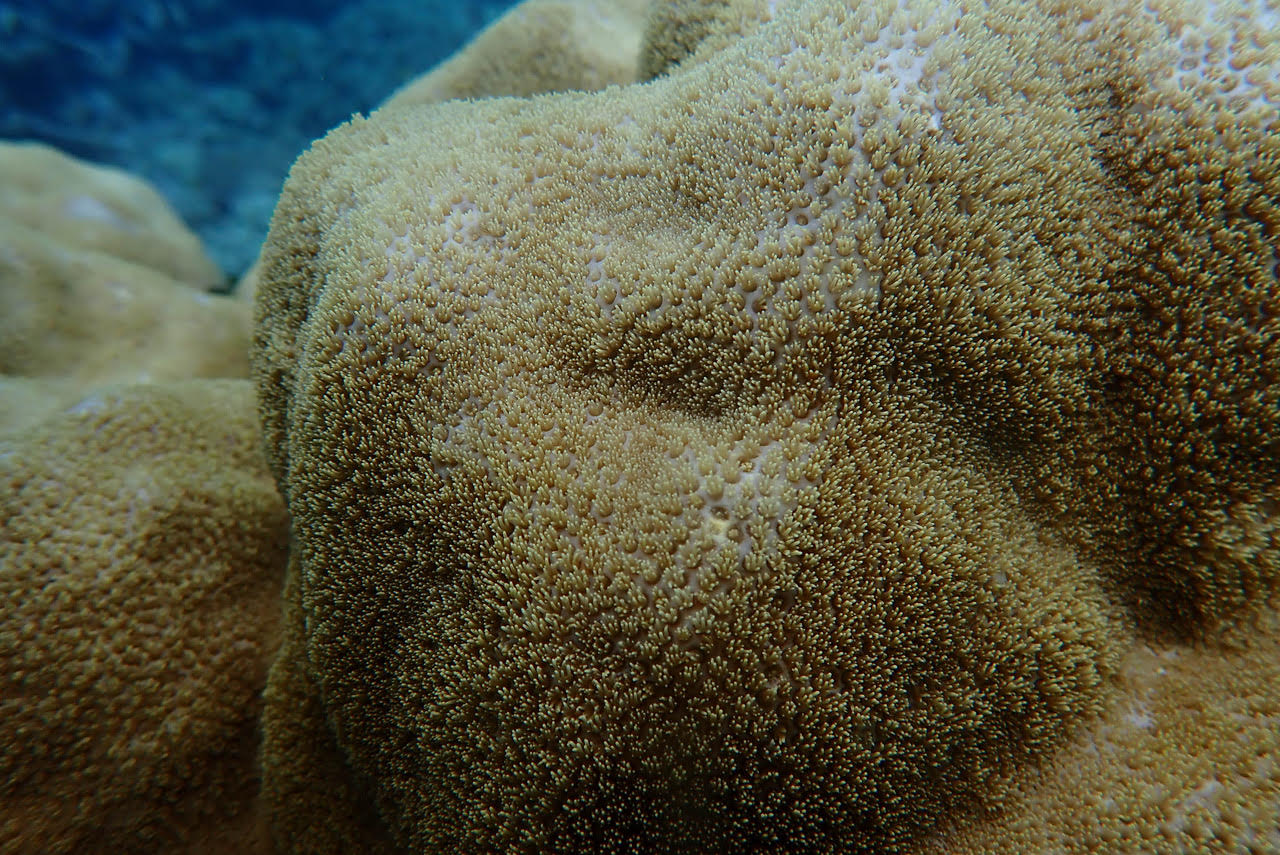

Fundamental to science is measurement. It is a way of objectively assessing something, anything, even the state of a coral reef, even of an individual coral. Historically coral growth rates were measured by coring the really old massive Porites.

Like tree rings in temperate forests, the massive old Porites can be cored to see the banding and from this it is possible to calculate coral calcification rates which are a measure of the growth rate of individual corals.

Peter Ridd has been asking for some quality assurance of so many of the measurements relating to Great Barrier Reef health, including coral growth rates. Key Australian institutions have responded by stonewalling, and in the case of James Cook University, actually sacking him. After two rounds in the federal courts his appeal against his dismissal is finally going to the High Court of Australia, with the next hearing probably in February 2021. While the lawyers are preoccupied with Peter’s rights, or otherwise, to academic freedom and freedom of speech, my concern is whether Peter is actually telling the truth when he says that the Great Barrier Reef is resilient and definitely not dying from coral bleaching, though there is a problem with the integrity of the science.

Most media reports, based on extensive aerial surveys by his one-time colleague Terry Hughes, conclude that the reef is variously 50% or 60% dead from coral bleaching as a direct consequence of global warming.

These media reports do not consider coral growth rates, but rather the area of coral that Professor Hughes has measured to be bleached, with an inference being that this will all die.

Terry Hughes and Peter Ridd can’t both be right.

How can they have come to such different conclusions regarding the health of the Great Barrier Reef? Is the reef really half dead, or not?

My working hypothesis is that Terry Hughes’ claims the reef is half dead, are not objective because there is a flaw with his particular survey method. This method is detailed in the technical literature, specifically his paper in Ecology published in 2018 entitled ‘Large-scale bleaching of corals on the Great Barrier Reef’.

Science is not a truth. It is a way of getting to the truth via some method or other that often involves measurement. Sometimes scientists get the method wrong, and so they come up with answers that are also wrong. Sometimes the wrong answer pleases because it is politically correct.

Could it be that in surveying by looking out the window of an aeroplane at such a high altitude (150 metres), and then ground truthing only with respect to a particular reef habitat-type known as the ‘reef crescent’, Professor Hughes has inadvertently recorded a wrong answer? Could he be avoiding, even in denial, when it comes to all the corals in the reef lagoon?

Marine scientists, and anyone with experience diving coral reefs, knows that there are distinct ecological zones at coral reefs. The reef crest, as the name suggests, is the highest part with corals in this habitat often exposed at low tides, sometimes rained-on, and during storms and cyclones this is the part of the reef that will be most likely smashed by big waves. Not surprisingly this habitat/area of a coral reef may be totally devoid of live coral or the coral may be more stunted, and sparse. At the same reef there may be healthy corals in the lagoon and back reef to the leeward side of the crest, and also corals growing down the front slope, even around the perimeter of the crest if it is a flat-topped platform. So, in only surveying the crest, the scientist/Terry Hughes could come away with the impression the reef is dead, when it is actually teeming with life – just not at the reef crest.

Professor Hughes specifically states in his 2018 article that underwater surveys were conducted to assess the accuracy of aerial surveys using five 10 x 1m belt transects placed on the reef crest. There is no suggestion that he distinguished between the different reef habitats. He only surveys the reef crest. He surveyed the area that probably had the ‘worst’ and ‘least’ coral.

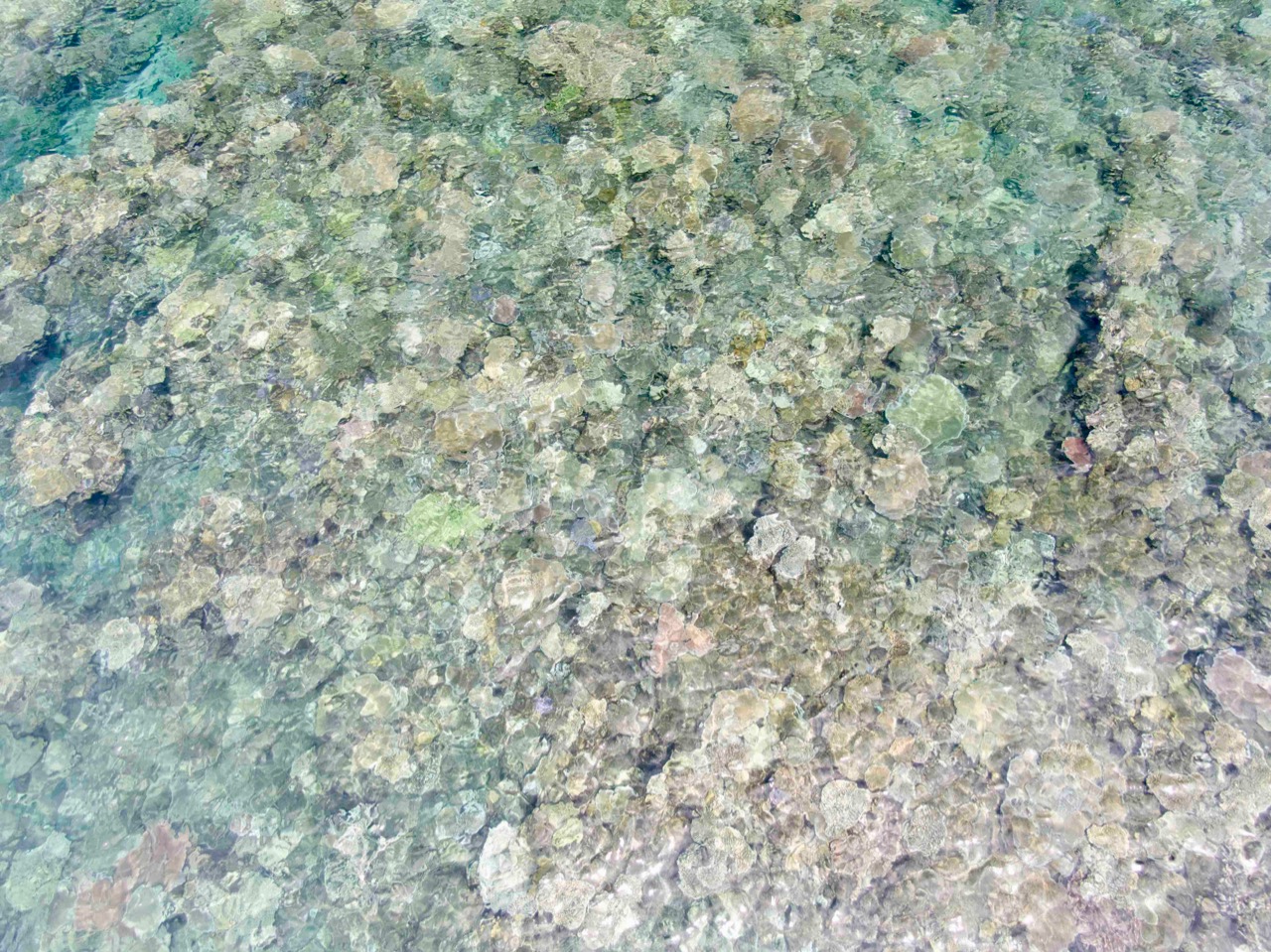

I tested my hypothesis that Professor Hughes’s methodology is flawed at Pixie Reef just two days ago (25th November). We put my drone Skido into the air and took photographs at 5, 10, 20, 40, 100 and 120 metres of altitude at the reef crest, reef lagoon and reef front slope. Following are photographs just at 5 and 120 metres and just from the crest and lagoon at Pixie Reef. (If I can get a large collection of these type of photographs together from different reefs, they could form the basis of a note for publication about measurement and the importance of measuring different habitat types at the same reef if the idea is to understand the health of the entire reef ecosystem, not just the reef crest.)

A photograph taken at 120 metres altitude of the reef crest is quite different from a photograph of the reef lagoon taken at exactly the same altitude. At 120 metres altitude parts of the reef crest looks rather barren, perhaps bleached. Hughes has mostly concluded that the Great Barrier Reef is 60% bleached from 150 metres looking out a plane window at the reef crest.

The rather large circular boulders in the lagoon photograph from 120 metres up are massive Porites corals. The type of coral that Peter Ridd would like AIMS to core, so we had an objective measure of coral growth rates back 100s of years.

The photograph of the reef crest from 120 metres altitude was taken with the drone (Skido of course) lifted vertically from 5 metres to 120 metres. This is what the same reef looked like at just 5 metres above the crest. There are live corals but no massive Porites or even red Gorgonians, though both exist at Pixie reef but would have been excluded from a 10 metre belt transect across the reef crest and from an aerial survey of the crest, because they exist in a different habitat type.

A photograph taken at 5 metres from above a section of reef lagoon shows plate corals, presenting as toadstools when photographed from under-the-water, which seems most appropriate given this is Pixie reef. I didn’t find any pixies though.

So much thanks to Stuart Ireland for taking me to Pixie Reef, and for taking all the photographs under-the-water, and he also flew Skido. All the photographs (except the shutterstock of the coring), were taken at Pixie reef on 25th November 2020. Pixie reef is just to the north east of Cairns in Far North Queensland.

****

The image at the very top of this blog post is of me/Jen swimming over the top of a 7 metre wide Porites at Pixie Reef on 25th November 2020. This is the type and size of coral that Peter Ridd would like to think was still being cored by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), as an objective measure of coral growth rates. AIMS used to core these old corals, to get an idea of climate change back hundreds of years. This coral could be more than 400 years old, with annual bands that can be measured at the scale of one year, year on year perhaps back 300 or 400 years to calculate an annual growth rate. So, from the one coral we could (if they cored it) see if growth rates have increased or decreased year on year, or not.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.