Many Australians are fearful of catastrophic human-caused climate change because this is what the state-sponsored propaganda on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (the ABC) tells us.

In Australia, we mostly live near the sea. All along our coastline there is evidence of sea level fall, yes fall.*

Where is the evidence for rising sea levels?

Will you see how much sea levels have risen when you watch the fireworks over the Opera House in Sydney Harbour this New Year’s Eve — or will you see evidence of sea level fall?

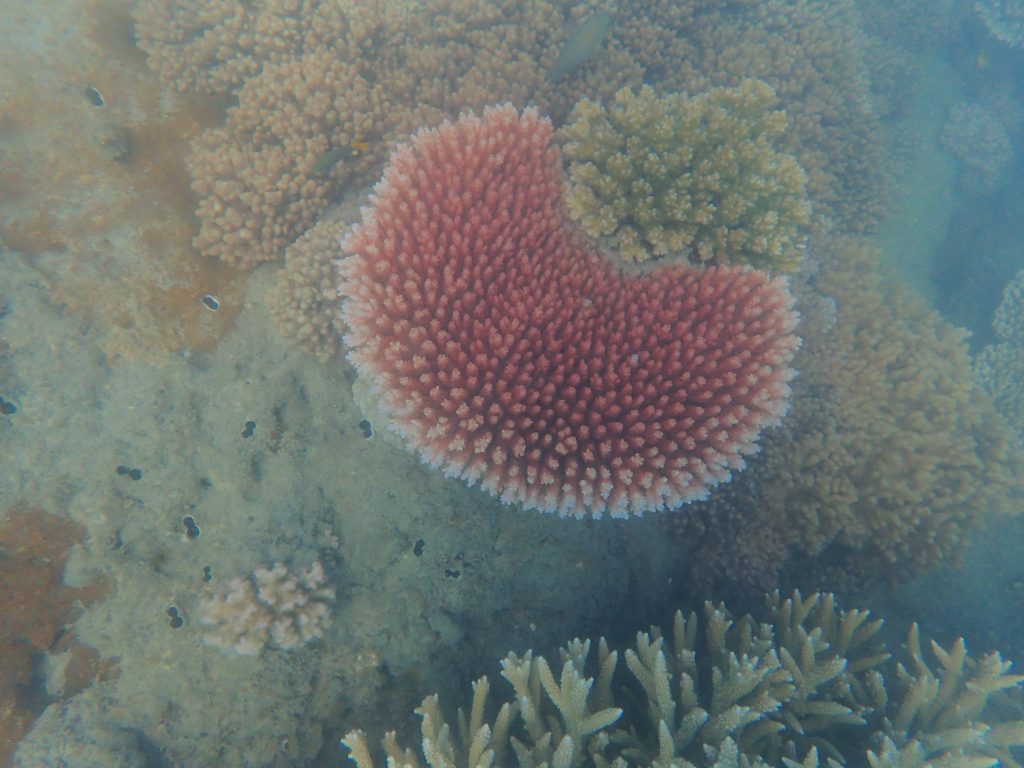

It is that time of year when family and friends visit me at the beach. My niece told me just before Christmas that she had read so many of the comments at the YouTube thread following my first short film ‘Beige Reef’. She was surprised at how many comments there were — an awful lot she commented.

When I asked her what she thought of the film, she told me that she had not actually watched the film.

At that morning tea, under a shelter at Coolum Beach, none of my nieces or nephews or older brother could admit to having watched the film.

It is all of 12 minutes long.

This first film involved me wading into, and diving below, waters that my sister-in-law some weeks earlier had indicated put me at risk of a shark attack. But still she has not actually watched the film.

I know that there is fear within the varies communities within which I exist, of at least three things: sharks, catastrophic human-caused global warming — and that I could lead some of them down the path of global warming scepticism and from this they could end-up pariahs.

I diverge.

The best evidence is that global sea level has fallen by at least 2 metres since the the Holocene high stand about 4,000 BC; that is about 6,0000 years ago, a time known as the Minoan warm period.

The evidence in rocks and cliff faces all along the Australian east coast is that sea level was about 1m higher in the Roman warm period (year 0), and about 0.5m higher in the Medieval warm period (1,000 AD).

Conversely, it is believed the sea level was lower in the cold periods of 500 AD (Dark Ages) and the Little Ice Age (1,650 AD), maybe both 0.2 — 0.5 metres below today’s level. This last low sea level is particularly important, because it from this base sea levels are perhaps still rising back to average Holocene levels. But are they really?

When I go kayaking, and walk along the sea shore, and send my drone Skido up into the sky and look down and take pictures of things like marine potholes that feature at the top of this blog post: I see evidence for a sea shore that is receding.

The sea begins at the land’s edge. Where the sea begins is the ‘sea level’.

When I stand beside the circular pothole that you can see in the centre of the picture accompanying this blog post (… scroll to the very top).

I’m standing on a wave-cut platform of sandstone bedrock with rectangular fractures, and red iron oxide colouring.

Potholes are formed by the relentless grinding of harder rocks — perhaps granite— caught in a depression in this softer sandstone. Pounding surf causes the harder rocks to swirl — round and round — grinding down.

The grinding that created these potholes could only have happened when sea levels were higher, when this platform was between the high and low tide marks.

I took the picture on a highest tide this last year, in 2019. A year that is nearly over.

Sea levels must have been higher in the past. Because even on the highest tides this last year, the waves never reached this far?

The ABC may be concerned about rising sea levels, but where is your evidence for it? Are you brave enough, do you care enough, can you find the time enough, to think through some of these issues this next year: in 2020?

We are all entitled to our own opinions, but not our own facts.

______________________

* This is intended as the first of a series of blog posts on sea level change.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.