I received the most delightful Christmas present: a poetry book published 7 years ago by Christian Bartholomew Wright.

I am not usually big on possessions — but books: I hoard them. A problem is that my whole life I have moved every so many years — to another place — and then I sometimes can’t find particular books any more. Which can be so annoying.

What is it about some books? What is it about some words? That I so love.

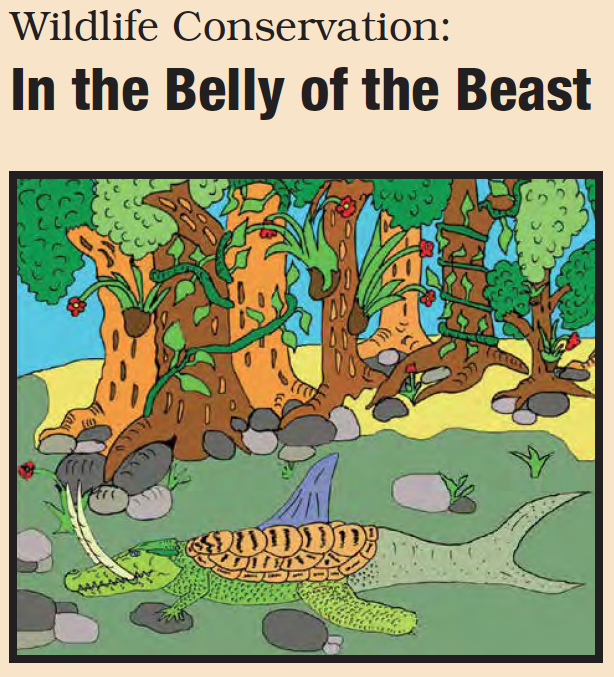

About 18 months ago — to be precise it was very early in the morning on 23rd June 2019 — I walked through Noosa National Park with my drone. I was planning to learn how to use some drone mapping software by programming Skido to make an interactive map of the rocks at Granite Bay.

I did make a map, though I can’t find it anymore. Then I sat on that beach and watched the waves. That morning the waves seemed to toss out lace, and then retracted it. I wondered, as I sat there, how would one ever describe the beauty of it, in words.

Then I received the poetry book this Christmas, and there are the words describing what I saw that morning, but with a changed context:

Books

.The sea is folding her dress, smoothing out the wrinkles.

She crochets her skirt in white foam doilies.

She pushes the hems down her legs

and pulls the slip up from her knees.

But in the ocean’s tired wash,

Her dress is threadbare and older than books.

My grandmother once taught me how to crochet doilies. I’ve no idea where they are now — the doilies. I also lose books, and maps filed on my computer. And the years, as we get older, they seem shorter.

After tomorrow it will be a new year. This year, I have at least found some words that I was looking for last year.

Happy New Year!

And may we always be allowed to just sit at the beach.

**********

The feature image (at the very top) is a photograph of me looking up at my drone at Granite Bay that morning, 23rd June 2019. And the picture (under the poem) has been clipped from one of the images taken by Skido (my drone) to make the map. I can’t find the map, but I more carefully filed the ‘lace’ and now I have some words for it.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.