It is World Ocean Day, an opportunity to learn more about the Great Barrier Reef and also artificial reefs in the Gulf of Mexico.

It is an injustice that turtles are blown-up in the Gulf of Mexico because American oil companies choose a particular and inappropriate method for undertaking surveys before setting explosives. If they did underwater, rather than aerial surveys, it would be difficult to ever justify blowing-up biological diverse artificial reefs that are old spent oil rigs. It is also an injustice when aerial surveys are undertaken to falsely conclude the Great Barrier Reef is more than 60 percent bleached, when underwater surveys give a completely different and true assessments. It is also an injustice that the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences (AIMS) had a perfectly good methodology for coring corals under-the-water and calculating an accurate overall average coral growth rates for the Great Barrier Reef, but then they changed the methodology and when the new methodology was shown to be flawed by Peter Ridd they did nothing about it. Last week I was told a new and better overall coral growth rate will soon be published for the Great Barrier Reef – but the methodology is not, and will not, be available for scrutiny, especially not to Peter Ridd who was sacked by James Cook University for suggesting there needs to be some checking – some quality assurance. Let me explain in more detail, including about the turtles.

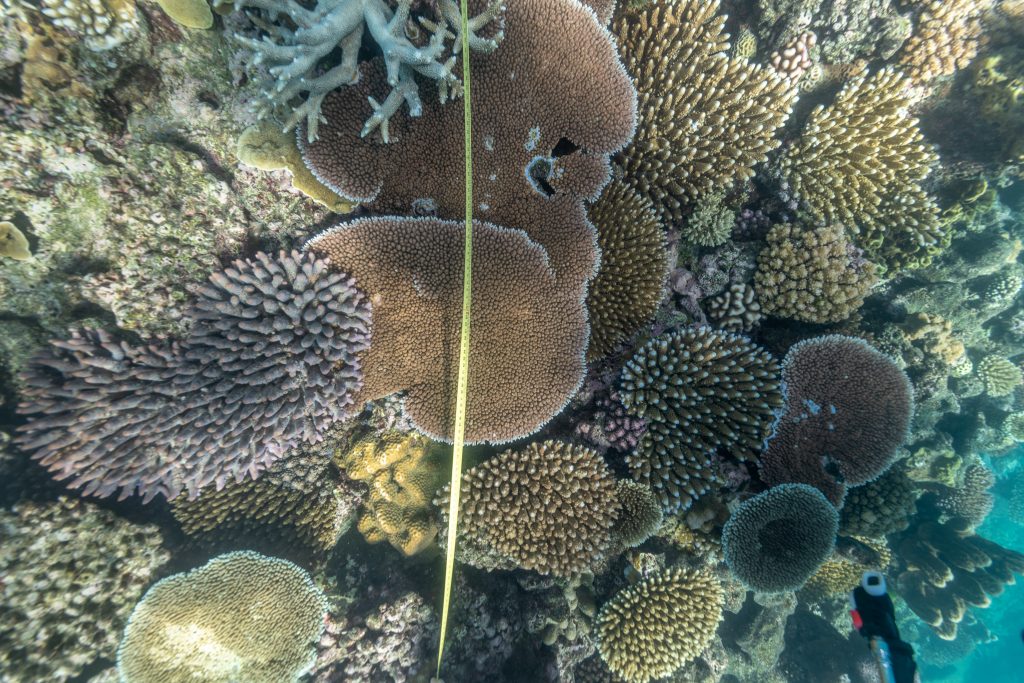

Late last year I went to sea for a week with Shaun Frichette. I’m a biologist, and I was searching for 400-year-old corals that can be 10-metres wide and have annual growth rings, like tree rings, they are in the genus Porites. Large and very old Porites corals used to be cored to calculate an overall coral growth rate for the Great Barrier Reef. Shaun came on the trip at short notice, wanting to know first-hand the state of the Great Barrier Reef; he had heard it was dying. He was working as a volunteer at a turtle rehabilitation centre on Fitzroy Island, which is just to the south-east of Cairns and part of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Ten years ago, he worked as a deep-sea diver in the Gulf of Mexico.

He got into deep sea diving in his late twenties because he had developed a passion for environmental issues especially marine conservation. At the time, he figured if an oil pipe was leaking on the sea floor it took a diver to go down and fix it, so he trained as a commercial diver and went to Louisiana. He did lots of diving on the oil rigs as well as working topside on saturation systems and diver tending. His goal at the time was to become a saturation diver and live life ‘like an astronaut’ except on the sea floor. To achieve that goal, Shaun knew he would have to put in years of hard work proving himself in the industry, but he never realized that the industry would meanwhile prove to care so little for life under-the-sea. For example, the oil companies, trained him to cut through steel with torches that burn at over 10 thousand degrees so that spent oil rigs could be dismantled safely – but instead they sent him down to the bottom of the ocean to plant explosives because it was faster to decommission a rig that way.

Shaun remembers:

The oil companies would send ‘turtle girls’ up in a helicopter to scout dolphins and sea turtles and if they gave the ‘all clear’ charges would go off and we would return to location. The problem was those oil rig platforms become like coral reefs after years of being submerged and the sea life around them is so biodiverse and special.

The turtle girls could only see 5 meters underwater on a good day so what I witnessed was horrific. Turtles cut in half, wounded dolphins and thousands of floating fish stunned from the explosions.

Something changed inside of me after seeing that and it’s altered my life path ever since.

Shaun quit and soon found himself back in California, in the High Sierra, at Lake Tahoe where he first learnt to Scuba dive. He bought into a dive business doing boat salvage and dock repairs during the summer months – while volunteering for marine conservation projects during the winter months when the lake froze over. The bushfires happened in Australia during the 2019-2020 ‘off season’ and after hearing news reports, Shaun volunteered as a fire fighter and came to Australia. Covid hit, and so he stayed-on. First helping with wildlife rescue, before travelling north to see the Great Barrier Reef.

I met Shaun late November 2020 at a café in Cairns. It was the day before we set-off with underwater photographer Stuart Ireland on a hurriedly arranged week at sea. The plan was to look for, and film, a particular type of coral known as Porites with annual growth rings, like tree rings, so they are potentially a time capsule of the ocean’s climate history. We wanted to find the oldest and largest of these corals that AIMS used to core, all the way to Myrmidon reef where there was once an extensive coral coring program.

Some of these Porites corals are huge. Just last year I measured a healthy Porites coral seven metres in width and three metres high, at an inshore reef called Pixie Reef just 40 kilometres to the northeast of Cairns. This is a reef that is classified in the peer-reviewed literature as one of the very worst bleached (more than 60%), yet I’ve struggled to find any bleaching at all at that reef. I’ve also seen Porites large and healthy, in fact dozens of them, in Bowen Harbour where all the corals are meant to be dead from global warming and ocean acidification and poor water quality – yet they are very much alive, or were, when I was there in April and then August 2019. Just three weeks ago at Lady Elliot Island to the east of Bundaberg I found a Porites that was 4 metres in height and so healthy. I asked the local divers if it has ever bleached and I was told by an old guy who has worked on the island for thirty years that it once went blue in colour after a cold snap, that was a few years ago, but that it has never bleached.

We are repeatedly told, most recently by the Australian Academy of Science, that most (somewhere between 50 and 99%) of the hard corals of the Great Barrier Reef are now dead yet this is not my experience as someone who snorkels and dives. I have seen very large and dead Porites, but not often. Perhaps as often as a I see a dead tree in my favourite national parks.

One of my frustrations with the official reporting on the health of the Great Barrier Reef is that much of it is based on aerial surveys. Not by turtle-girls, but by a university professor. Like the aerial surveys in the Gulf of Mexico, the surveys might be best described as convenient. They are certainly not scientific; despite being published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. The fly-past aerial surveys give the impression they are quantitative and claim that the entire Great Barrier Reef is more than 60% bleached, but the only numbers actually recorded by Professor Terry Hughes looking out the plane window are rankings of 1, 2, 3 or 4 based on his impression of the state of the corals from that high altitude.

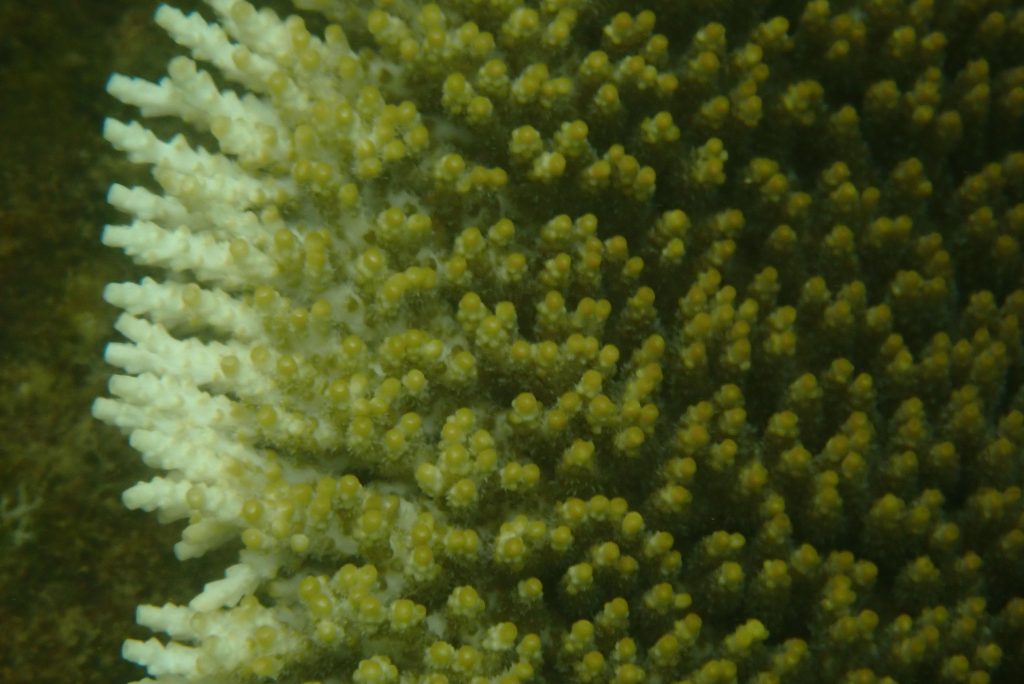

At 150-metres altitude he might be just able to just make-out the very large Porites at Pixie Reef on a good day. I sent my drone up and took photographs at 40 and 120-metres altitude of that monster coral that measures 7 metres in width on 25th November 2020. It appeared white and possibly bleached from the air. Yet under the water and up-close it was beige in colour, with healthy zooxanthellae. There was absolutely no bleaching. I gave the coral a score of D3 on the University of Queensland Coral Watch Health Chart (www.coralwatch.org). But who else actually goes to check?

To lament the dying Great Barrier Reef is politically correct, to question this is to risk being labelled a climate change contrarian. Yet my experience over 50 years of diving at the Great Barrier Reef – since January 2020 I have had the opportunity to SCUBA dive almost the entire length of the Great Barrier Reef from the Ribbon Reefs to Lady Elliot Island including dozens of reefs in-between – is that they are still exceptionally diverse and beautiful. The 2016 bleaching event was reportedly the most severe on record, particularly in the northern section including at the Ribbons Reefs, yet most of the reefs appear to be fully recovered.

When university professor Peter Ridd explained the extent of the misrepresentation back in 2015 in an email to a News Ltd journalist, specifically that there are still healthy live corals in Bowen Harbour, while calling out a colleague claiming otherwise, he was reprimanded by James Cook University. To publicly demand some quality assurance of claims the reef is dead and dying is professional suicide. The professor’s dismissal from James Cook University in 2018 – essentially on the basis that he broke the enterprise bargaining agreement by being un-collegial – has been appealed all the way to the High Court of Australia, with that hearing scheduled for 23rd June 2021. The Peter Ridd case is focused on issues of freedom of speech. Not because Peter does not care about the truth, but because the only way we might be able to get to the truth about the health of the Great Barrier Reef is if he can put his evidence – he needs to first have the opportunity to be heard beyond the academic journals that are behind paywalls.

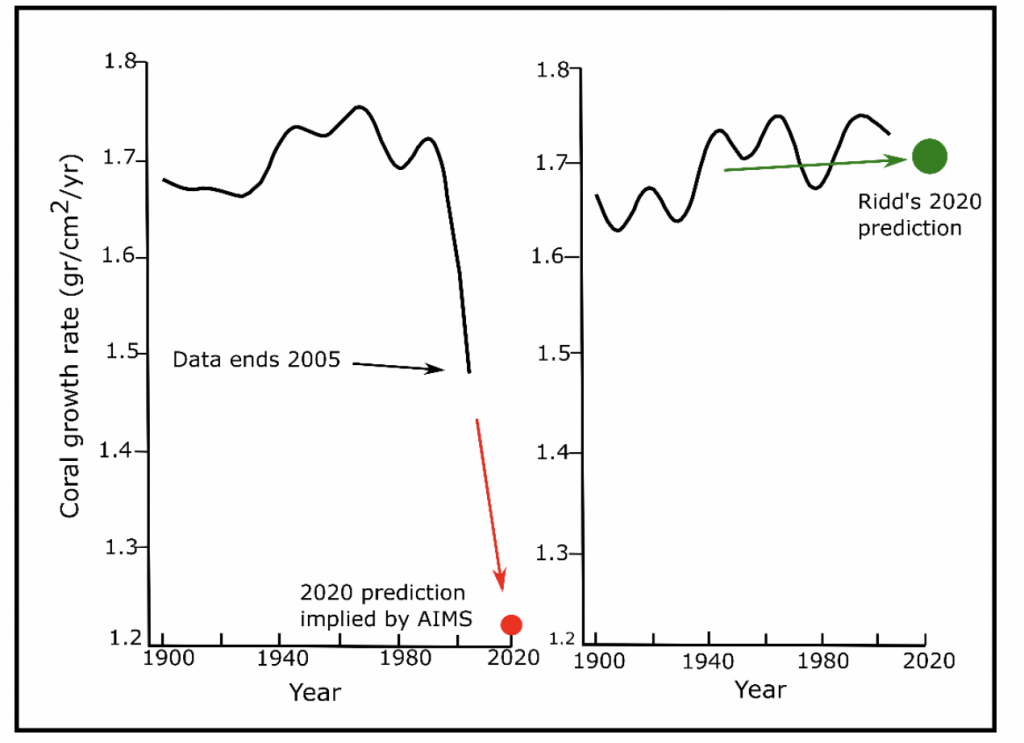

Back in 2013 Peter Ridd published an analysis of how the Australian Institute of Marine Sciences (AIMS) has changed the method they use for coring the Porites corals to calculate an average growth rate for the Great Barrier Reef. The method has essentially been changed for convenience. The data then showed a drop after 1990 that is conveniently consistent with the narrative that the Great Barrier Reef is dying – never mind that the new method is flawed.

Note: There is no data of the GBR-average growth rate since 2005.

In the 2013 research article in Marine Geology, Peter Ridd explains that firstly there are instrumental errors with the measurements of the Porites annual growth rings undertaken in the early 2000s. This is especially the case for the last layer at the surface of the coral, which was often measured as being much smaller than the reality. This created an apparent drop in the average calcification for the corals that were collected in the early 2000s – falsely implying a recent calcification (growth rate) drop. Secondly, an ‘age effect’ was not acknowledged, specifically the coring program in 2003, 2004 and 2005 focused on smaller colonies, many just a few tens of centimetres in diameter. In summary, while coring in the 1980s focused on large old corals and their growth bands were accurately measured, coring in the early 2000s focused on small young corals and when some of the measurements were checked they were found to be in error.

Yet the two datasets (from the 1980s and early 2000s) were spliced together, and wholly unjustifiable assumptions were implicitly made, but not stated – in particular that there is no age effect on coral growth. Coral growth rates are a potential measure of reef health, but the methodology needs to be consistent. When the data to 2005 is filtered for only the largest and oldest Porites corals, it shows an increase in calcification rates (coral growth rates).

I have made a short film about all of this: showing the Porites, how they used to be cored with archival footage, and also Peter Ridd is interviewed explaining the inconsistencies in the methodology. Towards the end of the film Peter Ridd is actually interviewed by turtle-man Shaun Frichette, and Shaun shows what we found during that week at sea last November all the way to Myrmidon reef in search of the oldest and largest Porites. Myrmidon is nearly 200 kms to the north north-east of Townsville. It is a detached coral reef exposed to the full force of the Pacific Ocean and to continual upwellings from the deep.

In the film we lament that the large old corals at Myrmidon are no longer cored by AIMS to know the climate history of this coral reef on the edge of the Pacific Ocean.

Last Thursday (3 June 2021), I received a phone call from an AIMS scientist, who told me that he still cores some of the old and healthy Porites. He claimed my new film is potentially misrepresenting the AIMS coring program.

I had been trying to talk with someone at AIMS about their coring program for months. In an email sent to AIMS director Paul Hardisty on 10 November 2020, Peter Ridd asked permission for me to film their largest and oldest coral cores and interview Janice Lough for my film – Peter Ridd began his career at AIMS in the 1980s, and was once a colleague of Janice, which was back when many of these cores were first collected. Paul Hardisty never replied to that email.

The scientist who phoned me last Thursday morning explained AIMS will soon be publishing a new overall coral growth rate for the Great Barrier Reef, and that the coring program has not stopped. I was appreciative of the phone call and asked to see the data since 2005 because in my new short film, Peter Ridd explains the coring program to calculate an average coral growth rate for the Great Barrier Reef stopped in 2005 – and that the data to this point is flawed.

In response to this request, I was sent a research paper about coring young Porites corals that was published in 2014, based on coral coring data collected in 2003, 2004 and 2005. I replied to the scientist that it is now 2021! Where is the data for the last 16 years – and how does the new data address the methodological issues detailed by Peter Ridd in his paper published in Marine Geology back in 2013?

What I found most interesting about the technical paper sent to me last Thursday afternoon, is that it laments coral bleaching as something that can cause a ‘growth hiatus’ in the large old Porites, but nowhere does it suggest coral bleaching actually kills these old corals. Also, the paper claims bleaching is a new phenomenon while presenting no data for the period before 1980. Yet AIMS has coral cores that date back to the 1600s, potentially providing 400 years of data including on the incidence of coral bleaching.

Deceit when it comes to issues of great public interest is not new. We have the choice as individuals to close our minds to new information that doesn’t necessarily accord with established narratives, or alternatively reflect on information that at a first glance appear anomalous. We are no better than those who choose to do aerial surveys knowing full well that turtles live under-the-sea, if we only hear and read that which accords with preexisting narratives that keep us conveniently connected to the status quo while misunderstanding the true state of the Great Barrier Reef. If we really care about something, we should want to know everything about it.

Today, on World Ocean Day, my short film starring both Peter Ridd and also Shaun Frichette, will premiere at The Majestic Theatre, in Pomona, not far from where I live. I am so grateful to the ninety people who have already bought their tickets. The bar opens at 2pm, the screening will be at 3pm.

Last Thursday I did extend an invitation to the AIMS scientist who phoned me, I suggested that he come to this screening. I explained that it would be possible to hold a questions and answers session after the screening, that we could even invite some local media so AIMS could clearly explain and hopefully show the last 16 years of data. I was told that this would not be possible.

On 10 June 2021, the IPA will premiere ‘Finding Porites’ on YouTube and also Facebook.

https://www.facebook.com/Inst.ofPublicAffairs/videos/1223155594867184/

***

The feature image, at the very top of this blog post, shows Jennifer Marohasy with a turtle at the Great Barrier Reef in April 2006.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.