We live in an era when it is politically incorrect to say the Great Barrier Reef is doing fine, except if it’s in a tourist brochure. The issue has nothing to do with the actual state of corals, but something else altogether.

Given that the Great Barrier Reef is one ecosystem comprising nearly 3000 individual reefs stretching for 2000 kilometres, damaged areas can always be found somewhere. And a coral reef that is mature and spectacular today may be smashed by a cyclone tomorrow – although neither the intensity nor frequency of cyclones is increasing at the Great Barrier Reef, despite climate change. Another reason that coral dies is because of sea-level fall that can leave some corals at some inshore reefs above water on the lowest tides. These can be exceptionally low tides during El Niño events that occur regularly along the east coast of Australia.

A study published by Reef Check Australia, undertaken between 2001 to 2014 – where citizen scientists followed an agreed methodology at 77 sites on 22 reefs encompassing some of the Great Barrier Reef’s most popular dive sites – concluded that 43 sites showed no net change in hard coral cover, 23 sites showed an increase by more than 10 per cent (10–41 per cent, net change), and 17 sites showed a decrease by more than 10 per cent (10–63 per cent, net change).

Studies like this, which suggest there is no crisis but that there can be change, are mostly ignored by the mainstream media. However, if you mention such information and criticise university academics at the same time, you risk being attacked in the mainstream media. Or in academic Dr Peter Ridd’s case, you could be sacked by your university.

After a career of 30 years working as an academic at James Cook University, Dr Ridd was sacked essentially for repeatedly stating that there is no ecological crisis at the Great Barrier Reef, but rather there is a crisis in the quality of scientific research undertaken and reported by our universities. It all began when he sent photographs to News Ltd journalist Peter Michael showing healthy corals at Bramston Reef, near Stone Island, off Bowen in north Queensland.

More recently, I personally have been ‘savaged’ – and in the process incorrectly labelled right wing and incorrectly accused of being in the pay of Gina Rinehart – by Graham Readfearn in an article published in The Guardian. This was because I supported Dr Ridd by showing in some detail a healthy coral reef fringing the north-facing bay at Stone Island in my first film, Beige Reef.

According to the nonsense article by Mr Readfearn, quoting academic Dr Tara Clark, I should not draw conclusions about the state of corals at Stone Island from just the 25 or so hectares (250,000 square metres) of near 100 per cent healthy hard coral cover filmed at Beige Reef on 27 August 2019. Beige Reef fringes the north-facing bay at Stone Island.

This is hypocritical – to say the least – given Dr Clark has a paper published by Nature claiming the coral reefs at Stone Island are mostly all dead. She based this conclusion on just two 20-metre long transects that avoided the live section of healthy corals seaward of the reef crest.

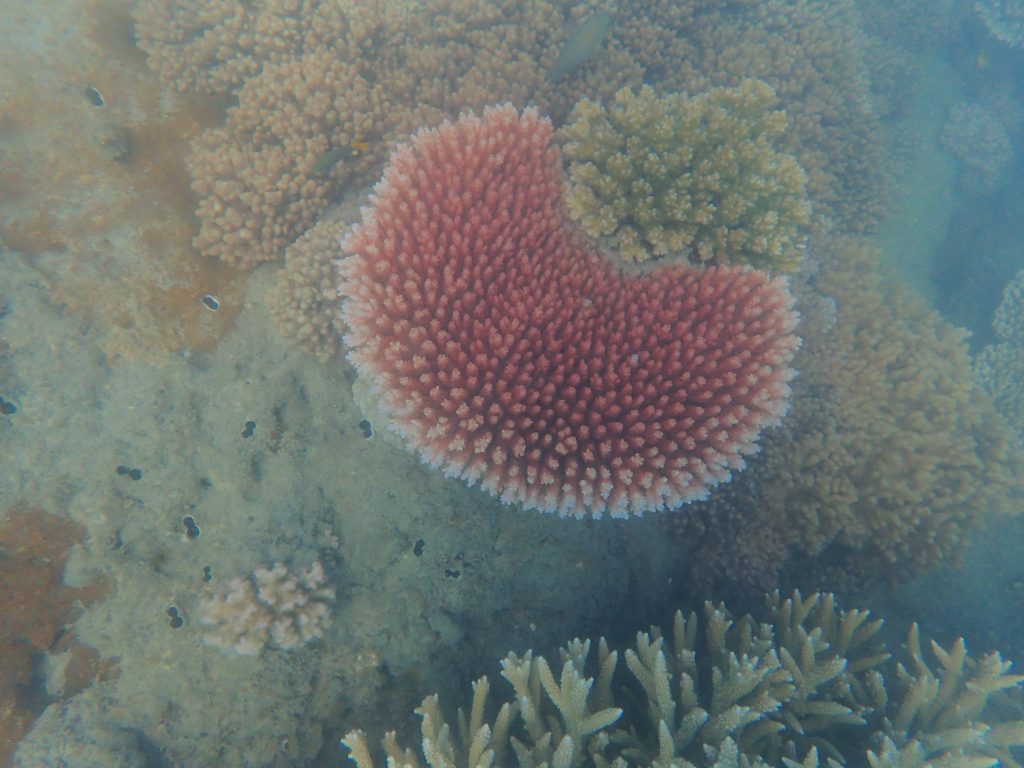

I will refer to this reef as Pink Plate Reef – given the pink plate corals that I saw there when I went snorkelling on 25 August 2019.

Dr Clark – the senior author on the research report, which also includes eight other mostly high-profile scientists – is quoted in The Guardian claiming I have misrepresented her Great Barrier Reef study. In particular, she states,

We never claimed that there were no Acropora corals present in 2012.”

Yet this is really the only conclusion that can be drawn from the information presented in her report, which states in different sections the following:

Using a combination of anecdotal, ecological and geochemical techniques, the results of this study provide a robust understanding of coral community change for Bramston Reef and Stone Island.”

At Stone Island, the reef crest was similar to that observed in 1994 with a substrate almost completely devoid of living corals.”

For Stone Island, the limited evidence of coral growth since the early 19th Century suggests that recovery is severely lagging.”

… by 1994 the reef was covered in a mixture of coral rubble and algae with no living Acropora and very few massive coral colonies present …”

Clark and colleagues recorded the corals along two transects, which they explain included a section of the reef now stranded above the mean low spring sea level. The sections they studied are some metres away from healthy corals – Porites and Acropora species, including pink plate corals that I snorkelled over on 25 August 2019.

Fringing inshore reefs often show distinct zonation, with live and healthy corals growing along the seaward edge. At Pink Plate Reef, the reef edge extends for some 2 kilometres and is about 20 metres wide in parts, while much narrower in other sections.

on 26th August 2019.

The more inshore section of such fringing inshore reefs, sometime referred to as ‘the lagoon’ between the beach and the reef edge, is usually muddy. This mud has a terrestrial origin. From the lagoon towards the seaward edge there may be an elevated section, which is often referred to as the reef crest.

It is uncontroversial in the technical scientific literature that there has been sea-level fall of about 1.5 metres at the Great Barrier Reef since a period known as the Holocene High Stand thousands of years ago.

It is also uncontroversial that sea levels fall with the El Niño events that occur regularly along the east coast of Australia most recently during the summer of 2015–2016.

As a consequence, the reef crest at many such inshore fringing reefs may end up above the height of mean low spring sea level. This is too high for healthy coral growth; because of sea-level fall, corals in this section of these reefs are often referred to as ‘stranded’ and will be dead.

Dr Clark and colleagues clearly state that they began their transects at Stone Island at the reef crest, which they also acknowledge is at ‘the upper limit of open water coral growth’. It could reasonably be concluded that Dr Clark’s study set out to sample the section of this reef that could be referred to as stranded.

Our society places enormous trust in scientists. It is as though they are the custodians of all truth.

Yet, as recently reported in another article in The Guardian by Sylvia McLain on 17 September, entitled ‘Not breaking news: many scientific studies are ultimately proved wrong!’, most scientific studies are wrong because scientists are interested in funding their research and their careers rather than the truth.

So, while another The Guardian journalist, Graham Readfearn, may look to scientists like Dr Clark and colleagues to know the truth about the Great Barrier Reef, reef scientists may be inclined to report what is best for their career in the longer term. This is increasingly likely to be the case, given the recent sacking of Dr Ridd for daring to speak against the consensus.

This could also to be the case for film makers. The Guardian has reported my honest attempts at showing how beautiful and healthy one of the fringing coral reefs at Stone Island is – including through spectacular wide angle underwater cinematography – the headline:

Scientists say rightwing think tank misrepresented her Great Barrier Reef study”.

This was the headline in The Guardian on Tuesday, accompanying the first review of my first film – Beige Reef. Many of the comments at YouTube now uncritically link to this misinformation.

It is not easy telling the truth when it comes to the state of corals at the Great Barrier Reef.

In my film Beige Reef, I show such a diversity of beautiful hard corals including species of Acropora and Turbinaria under dappled light at Beige Reef, which is a true coral garden fringing the north facing bay at Stone Island.

Meanwhile, Tara Clark and colleagues – lauded by journalists such as Graham Readfearn – write in their study published by Nature: ‘Only nine dead corals were found along transects 1 and 2, and that these corals were covered in mud and algae.’

Such a statement is perhaps politically smart, because it plays to the current zeitgeist that suggests humankind is having a terrible impact – destroying the planet everywhere, including at the Great Barrier Reef. So, the beautiful reefs that do fringe Stone Island – not just Beige Reef in the north facing bay, but also the reef along the south western edge, the reef that I’ve name Pink Plate – must be denied.

It seems an absolute tragedy to me that the beauty and resilience of these healthy coral reefs is not acknowledged. Further, the idea that the Great Barrier Reef is in peril creates tremendous anxiety throughout our community, particularly for the younger generation.

In another part of the same report, Dr Clark and colleagues state that coral cover was 0.09 per cent at Stone Island. This is not consistent with their ‘benthic survey’ only finding nine dead corals, and is certainly a lot less than the near 100 per cent coverage that I found at Beige Reef just around the corner. It is also a lot less than would have been found if their transects had been placed in that section of Pink Plate Reef with living corals – the section of reef at the seaward edge that extended for perhaps 2 kilometres.

********

Pink Plate Reef will be the focus of my next short film.

My travel to Stone Island and the film were funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation through the Institute of Public Affairs.

I snapped the picture of the sailing boat with Gloucester passage in the background, as featured at the top of this blog post, from Pink Plate Reef in the early afternoon on 25th August 2019.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.