Peter Ridd’s trial was set-down to be heard over three days next week, beginning on Monday 12th November. Many of us have made plans to travel to Brisbane – booked and paid for accommodation – to simply be there, to support Peter as he takes on the institutions in his fight for truth, and some quality assurance of Great Barrier Reef science.

I’d been told that the case would be heard by Judge Jarrett, who presided over the proceedings earlier in the year. Now I’m told it’s all been cancelled, at least for the moment – and that Peter can wait until next year, that his case against unfair dismissal by James Cook University might be heard next year.

Over the last week I’ve posted four articles at my blog.

1. ‘Peter Ridd and the Clowns of Reef Science’ is an introduction to some of the issues, taking a bigger picture view.

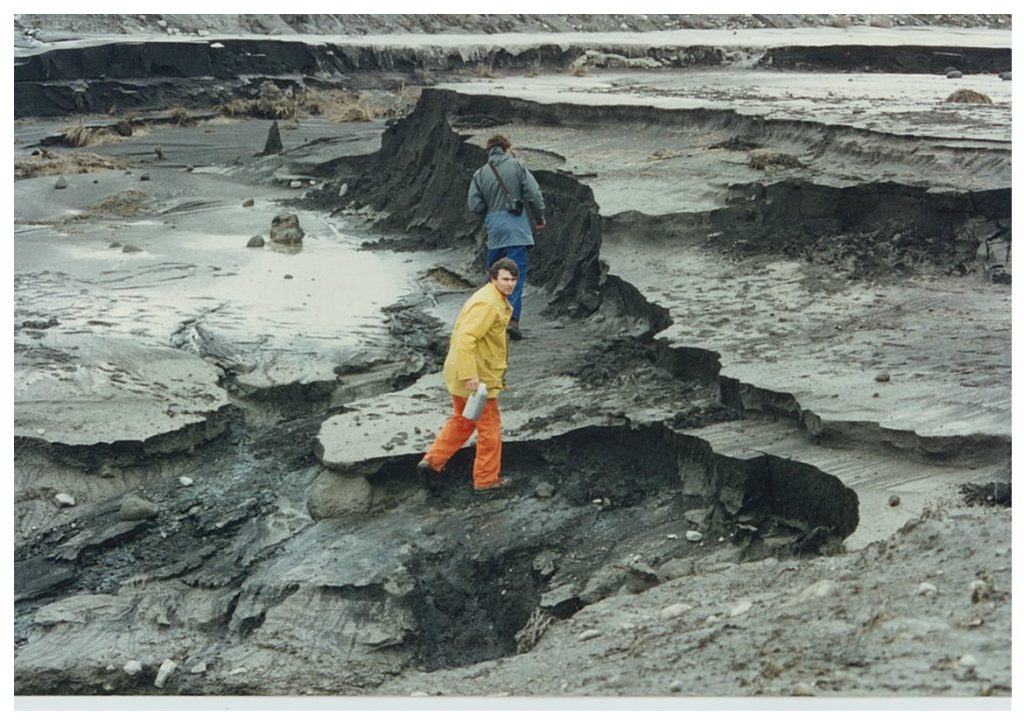

2. ‘No Mud on my Barnacles’ is for those who like natural history and would like to understand more about me, and the mud at north Queensland beaches.

3. ‘The Prince and His Dump Truck’ is about some of the personalities behind the WWF ‘Save the Reef Campaign’ that was launched in June 2001 – including Willem-Alexander, now the King of Holland.

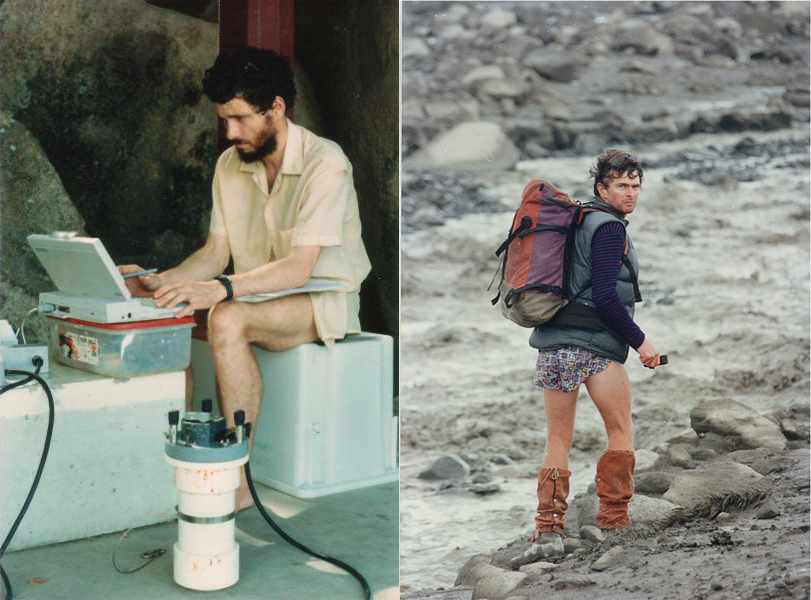

4. ‘Denying Comment from Experts, from the Marine Geophysical Laboratory’ is about Peter, and also Ken Woolfe who died tragically on 1 December 1999.

I’m hopeful these articles provide some background information – and also encouragement to Peter, who now must suffer through Christmas and the New Year with his life-on-hold.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.