MORE people died in Australia from extreme heat events in 1896 than in any other year, with 450 dead nationally. The second worst year was 2009 with 432 dead, followed by 1939 with 420. Considering these numbers in terms of total population, then we have a decline from about 13 dead per 100,000 in 1896, to 6 per 100,000 in 1939, to just 2 per 100,000 in 2009.

That’s according to a new paper by Lucinda Coates and colleagues from Risk Frontiers, Macquarie University and the Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre, Melbourne. The paper is entitled, ‘Exploring 167 years of vulnerability: An examination of extreme heat events in Australia 1844-2010’, and published by Environmental Science and Policy (volume 42, pages 33-44).

Coates and colleagues indicate that since 1844 extreme heat events in Australia have killed at least 5,332 people. Most deaths have occurred in January, and within January, most deaths occur on 27th January, which is the day after our national Australian Day holidays.

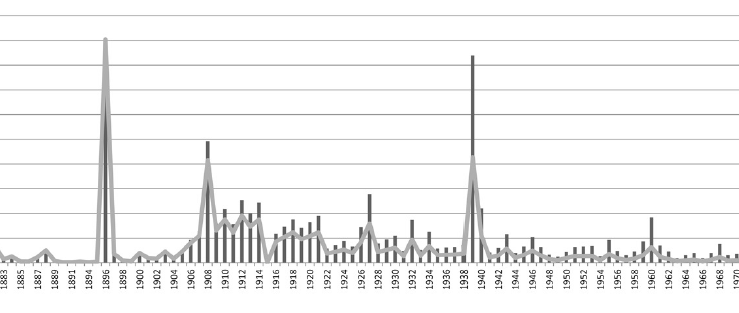

There are spikes in the total number dead, and also death rate in 1896, 1908 and 1939, Figure 1.

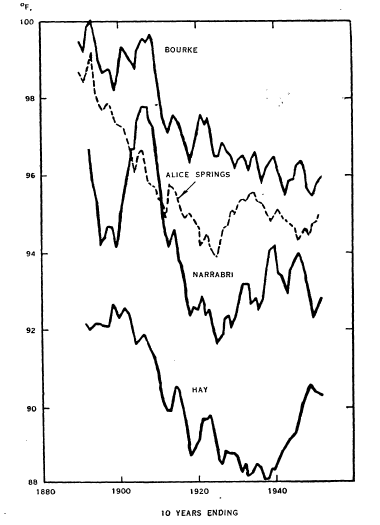

High death rates in 1912, 1914, 1927 and many years in between, suggest higher mortality due to extreme heat events during the early 20th Century. This is consistent with early publications on temperature trends in Australia. For example, a 1953 paper by E.L. Deacon (Australian Journal of Physics, volume 6, pages 209-218) shows the ten-year running average of mean summer maximum temperatures for several locations in central and eastern Australia peaked in the late 1800s, Figure 2.

This is generally consistent with the unhomogenized temperature record for eastern Australia (see for example Jennifer Marohasy et al. The Sydney Papers Online, Issue 26).

Apparently ignorant of this early publication by Deacon, and the unhomogenized temperature record for Australia, Coates et al. do not make the link between the higher death rate in the early 20th Century and the higher temperatures.

Rather, relying on recent reports from the CSIRO and Bureau of Meteorology, they simply state that since 1950 each decade has been warmer than the previous. While technically correct, such a statement ignores the very hot decades of the late 1800s and early 20th century and as such is misleading.

Coates goes on to state that, “Without adaptive measures, the conjunction of expectations for extreme heat events to be of greater frequency, duration and intensity and an ageing and increasing population suggests an increase in future heat-related fatalities.”

They attribute the fall in the decadal death rate from 1.69 deaths per 100,000 population in the 1910s to 0.26 in the 2000s to a “variety of factors, but mainly to reduced numbers of people working outside, a better informed public, greater freedom of dress and improvement in utilities and services, such as home cooling, access and breadth of health services including aged care services, warning systems and rescue services.”

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.

Jennifer Marohasy BSc PhD has worked in industry and government. She is currently researching a novel technique for long-range weather forecasting funded by the B. Macfie Family Foundation.